ASEAN growth opportunities following US-China Tariffs

The Trump administration’s tariffs have reshaped the geography of global production, and nowhere is this more evident than in Asia. China has borne the brunt of tariff increases, facing an effective rate of 41%—roughly double that of most ASEAN economies. This sharp disparity has created a powerful incentive for producers to move production capacity into other countries in Southeast Asia. As China continues to climb the value chain and domestic cost pressures rise, the gravitational pull of ASEAN’s competitive advantages—especially in labour-intensive and mid-tech manufacturing—is accelerating.

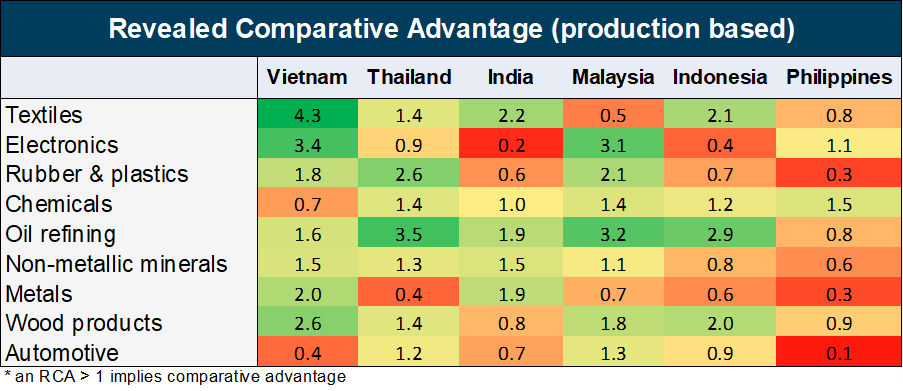

The question remains, however, where production will move next and what sectors will lead the transition. A useful tool for understanding this shift is Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA), a ratio that compares how important a sector is to a country’s economy relative to its importance globally. An RCA above 1 signals that a country has the embedded capabilities, supplier networks, and labour force to scale further in that sector. In an era of tariffs, nearshoring, and tech decoupling, this kind of evidence-based mapping points to where capacity can move most efficiently—and where policy support might have the greatest impact.

Using sectoral production data from Oxford Economics’ Global Industry Service, we have been able to quantify which countries and sectors have the greatest potential for production migration. Applying this framework across Asia reveals meaningful industrial depth in Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia in trade-intensive segments, and a distinctive, more resource-heavy footing in Indonesia and India.

Industrial depth across Asia offers scope for production migration from China

Malaysia’s edge lies in the combination of a mature high-tech ecosystem and natural resource–linked processing industries. Electronics is the standout, as Malaysia has long had a presence in the global semiconductor and device supply chain. Anchored by the Penang cluster—which is often nicknamed the “Silicon Valley of the East”—Malaysia is emerging as a credible alternative for semiconductors and devices production, which are at the heart of US–China trade tensions. At the same time, upstream strengths in oil refining, petrochemicals, chemicals, wood products, and rubber give Malaysia a diversified industrial base that can support deep, resilient supply chains. Malaysia’s leadership in rubber, which feeds into automotive components, medical devices, and construction materials, further strengthens its role.

Thailand has one of Southeast Asia’s most diversified manufacturing landscapes. Long and deep supply chains around car production underpin broader industrial activity, and the country is increasingly emerging as a regional production base for Chinese battery electric vehicles exported across Asia. Natural rubber is another pillar, with Thailand accounting for roughly a third of global output. This abundance supports highly integrated downstream industries, from tires to hoses to plastic components, which in turn are aided by an established petrochemicals sector. Strong logistics infrastructure, a reasonably stable policy environment, and its status as a founding ASEAN member all reinforce Thailand’s appeal as a destination for capital-heavy, complex production migrating out of China.

Trade uncertainty continues to cast a shadow for APAC industry – Unlock exclusive insights in our recent webinar.

Vietnam continues to be one of the most compelling alternatives to China for global manufacturers looking for both scale and specialisation. Its industrial base spans low- to mid-value-add segments, with revealed comparative advantage in textiles, rubber and plastics, metals, wood products, and electronics. As US tariffs on Chinese apparel bite, Vietnam’s factories provide a more economical and geopolitically diversified option, particularly for consumer goods that prize speed and cost.

Over the past 15 years, Vietnam has become a major producer of consumer electronics, supporting key global brands and advancing into components, semiconductors, and printed circuit boards. Vietnam is on its way to becoming the largest ASEAN exporter of electronic products to the United States, with an export value of $59 billion in 2024. This compares to just $1 billion in 2011. With trade restrictions reshaping Sino–US technology links, Vietnam’s electronics exports to the US are on track to eclipse China’s US-bound electronics shipments as early as 2026.

Indonesia’s strengths are different in profile. The country’s industrial edge is grounded in abundant natural resources—timber, fossil fuels, and agricultural products—that support well-integrated petrochemicals and resource-processing value chains. Indonesia maintains export competitiveness in textiles and garments thanks to favourable labour costs, which is putting it in a strong position it to win market share from China in low-complexity, labour-intensive production. However, Indonesia’s transition into higher-value, export-oriented manufacturing remains constrained by structural and regulatory frictions. Hence, it is more likely that the country will emerge as a regional hub for lower-complexity production—especially in sectors resource inputs and labour intensity dominate—rather than rapidly replicating China’s manufacturing model.

India sits somewhat apart from the Southeast Asian narrative. Its revealed comparative advantage is concentrated in heavy industrial sectors like petrochemicals, metals fabrication, non-metallic minerals, and oil refining. These industries are capital intensive and tend to be more domestically oriented rather than globally tradable, which limit the near-term benefits from tariff-driven production shifts aimed at the US market. Textiles are the clear exception: India has an established, highly tradable garment and apparel sector that could expand to serve US demand as Chinese exports face higher barriers. Over the longer term, the strength of India’s heavy industry can provide a foundation for downstream, higher-value manufacturing. Yet, persistent hurdles—from land acquisition challenges to logistics costs—continue to complicate efforts to capture capacity migrating out of China, even as recent changes to the GST have simplified parts of the tax landscape.

From Arbitrage to Advantage: Securing ASEAN’s Industrial Future

Taken together, the picture is of a region in transition, propelled by both policies and economics. Tariff differentials have catalysed change, but they are not the only force at play. China’s own development path, toward higher-value production and rising wages, would have encouraged supply chain diversification even without US tariffs. Low-wage economies in ASEAN are natural beneficiaries of this shift, particularly in labour-intensive sectors where cost remains decisive. At the same time, countries with established industrial ecosystems and upstream strengths, such as Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand, are best placed to absorb more complex, capital-intensive activities.

For businesses, this implies looking beyond headline tariff rates and instead focusing on the depth of local ecosystems, the reliability of logistics, and the alignment between product complexity and country capabilities. For policymakers, the moment calls for targeted investments in infrastructure, skills, and regulatory clarity to convert short-term trade arbitrage into long-term industrial advantage. The redirection of supply chains is already underway—the winners will be those that can marry opportunity with readiness, leveraging existing strengths to capture the next wave of production moving out of China and into a more multipolar Asian manufacturing landscape.

How can your business navigate the emerging opportunities?

Industries are navigating a perfect storm of trade volatility, protectionist tariffs, and supply chain reconfiguration. At Oxford Economics, we help you track activities in your downstream demand sectors and anticipate market shifts under a range of scenarios.

Request a trial of our Global Industry Service and gain access to forecasts, scenarios and expert insight into the latest industrial economics’ developments today.

Tags:

Related Reports

Peak tariff impact on industry still to come

In 2026, we anticipate global industrial value-added output to grow just 1.9%, the slowest pace of growth since the global financial crisis.

Find Out More

European defence spending surge: which sectors will benefit?

Our modelling suggests the main beneficiaries of the spending will be a highly concentrated subset of capital-intensive subsectors, mainly in transport and electronics.

Find Out More

Global Pump Market Outlook 2025

In 2025, we are expecting a deceleration in global pumps demand to 1.0% as the global economy contends with new headwinds.

Find Out More

US-China relations improve, yet industrial recession remains likely

For the first time this year, our global industrial production outlook for 2025 has been upgraded. However, we still anticipate an industrial recession in Q2 and Q3.

Find Out More