COP30 in focus: The economic cost of a warmer world

By Geoffroy Dolphin and Daniel Parker

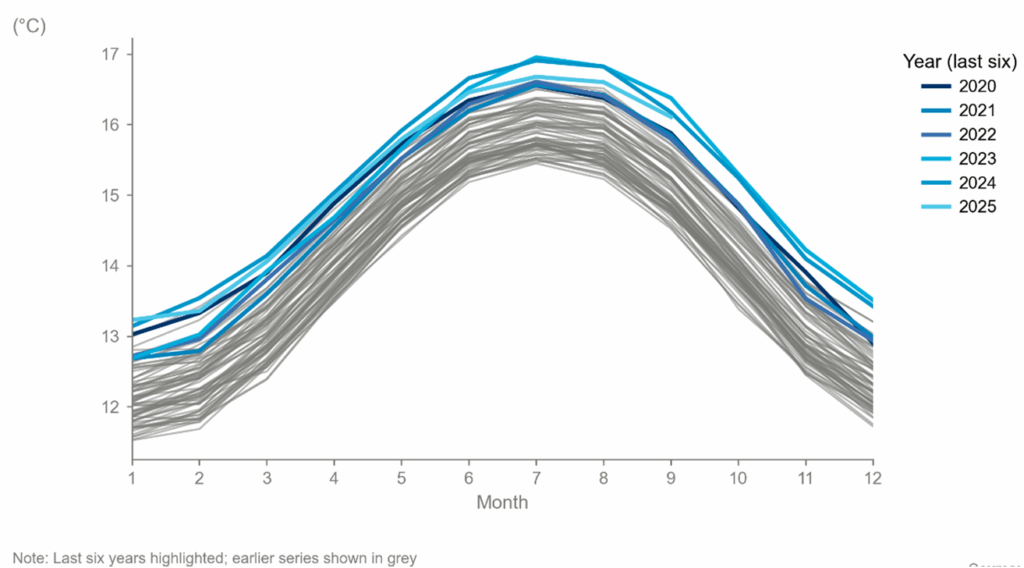

As delegations prepare to meet in Belém next week, the global climate continues to change. Every month over the past five years has ranked among the warmest on record (Chart 1), and by September 2024, the Earth’s average temperature had risen by about 1.4 °C above pre-industrial levels (Copernicus).

Chart 1: Monthly Air Surface Temperature by Year – World

But the warming we see today is only the tip of the iceberg. More warming is already locked in—from recent emissions whose warming effect is not yet fully reflected in global temperature, and from countries’ projected emissions under their current policies, as evidenced by the latest Emissions Gap Report. What does this mean for the planet’s natural systems and our economies?

Let’s start with the physical science. While fluctuations in the Earth’s climate system are inherent to its history, the pace of the ongoing change is not. Since the end of the last Ice Age, global temperatures have fluctuated around a relatively stable mean and the distribution of temperature anomalies, i.e., differences from the reference climate, remained stable. That stability has now vanished. Since 1950, temperatures have increased by 0.02 °C per year on average, roughly 10 times faster than the warming that followed the last Ice Age.

These global averages hide a more complex and, in some cases, more daunting picture. Temperature rises are not only highly uneven across world regions—Europe, for instance, is warming approximately twice as fast as the global average, they also differ starkly between urban and rural environments, with cities warming more than surrounding regions due to the urban heat island effect.

How does global warming impact the economy?

The physical impacts of climate change are now clearly evidenced, visibly alarming and affecting millions of lives and livelihoods. Yet their macroeconomic implications, though equally significant, remain harder to pin down.

Despite substantial efforts in recent years, econometric studies still differ substantially in their estimates of how much climate change could cost the global economy. This variation largely reflects two key differences in approach.

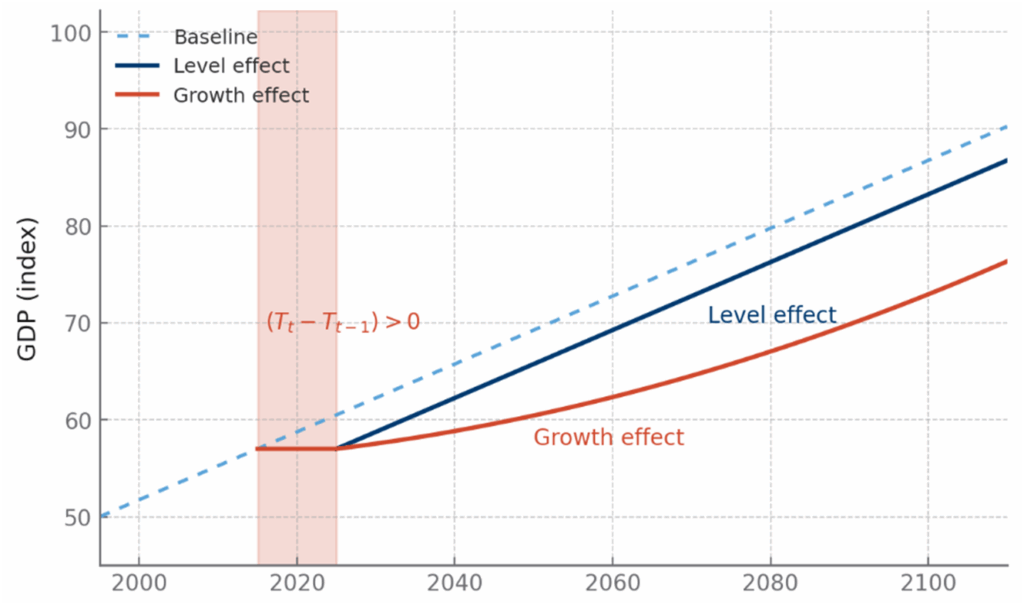

The first difference is whether additional warming affects (i) the level of GDP or (ii) its growth rate (Chart 2). In the first case, warming has a transitory impact, whereas in the latter it has a permanent effect on GDP as the losses compound over time. Early studies that relate temperature to GDP levels obtain relatively small loss estimates; more recent studies that relate temperature to GDP growth show that a shift to a higher temperature reduces GDP significantly compared to a ‘no further warming’ baseline.

Unlock exclusive climate and business insights—sign up for our newsletter today

Chart 2: The effect of a one-off temperature increase is larger if it affects economic growth

The second difference is the specification of the relationship between warming and economic output. Earlier studies that focus primarily on the impact of changes in the mean of climatic variables and do not account for the effect of their variability or frequency of extreme-weather events substantially underestimate the GDP impact of climate change.

Our analysis, which relates the full shape of the temperature anomaly distribution to GDP growth, suggests that a 2 °C change in global mean temperature—the median temperature change forecast by the IPCC climate model ensemble under the SSP3-RCP7 (business as usual) scenario—could lead to a 10-30 percent decline in global GDP in 2050, depending on how much more frequent extreme-weather events become.

This underscores a critical observation: projections of climate variability and frequency of extremes become an essential determinant of the estimated total damage.

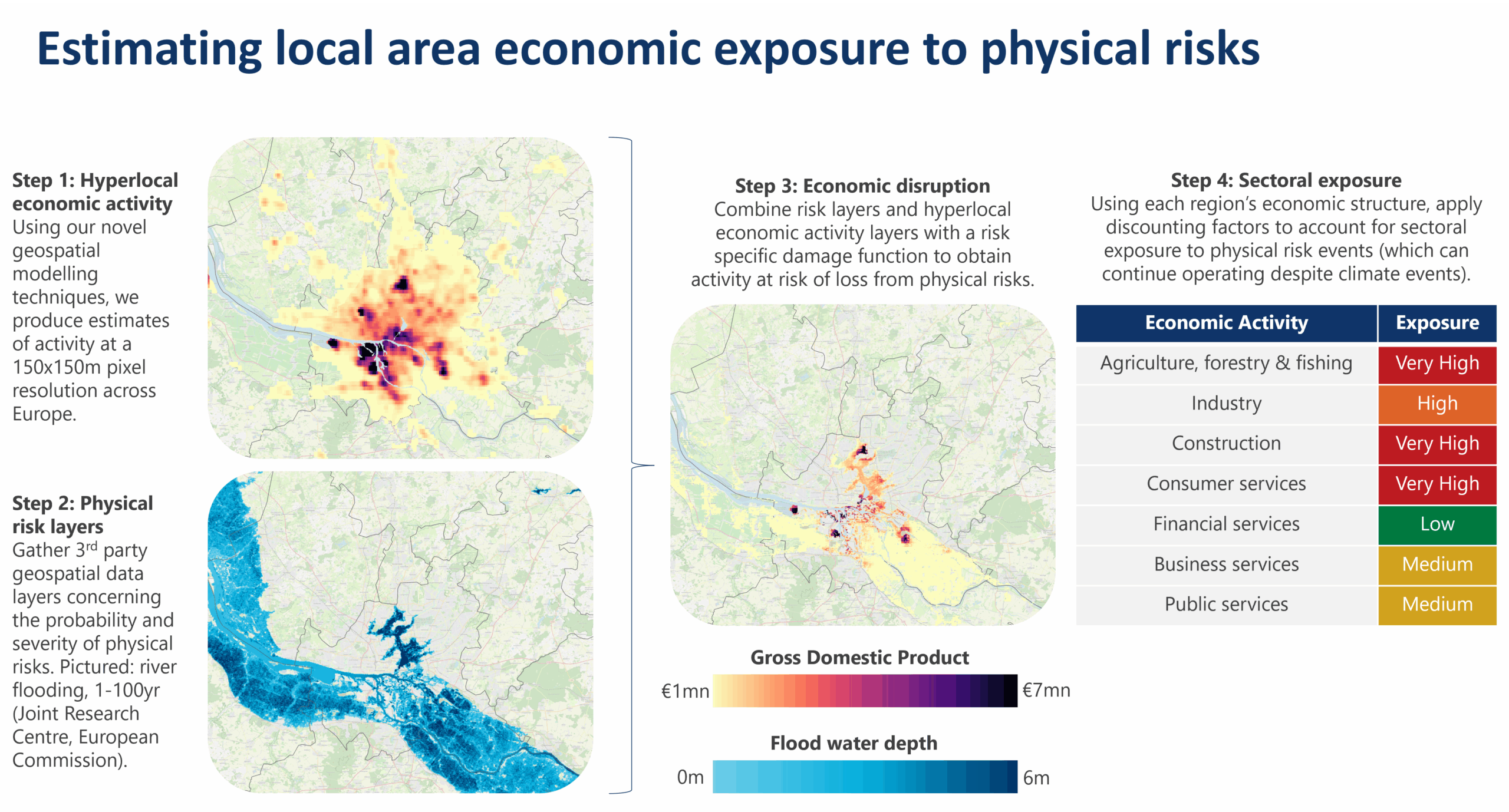

A characteristic of these extreme events is that they can be very localised, calling for a granular analysis of climate impact risks. Our analysis shows that potential impacts vary not only across subnational regions, but also within cities themselves. Combining data on the likelihood and severity of events, such as floods, heatwaves, storms, and droughts, with hyperlocal economic modelling clearly indicates that national or regional averages can mask important differences (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Estimating local area economic exposure to physical risks

Take major European coastal and riverside hubs, for example. Cities such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Hamburg are naturally exposed to flooding, but the economic impact depends on the type of activities located in vulnerable areas. In Hamburg, the low-lying north along the Alster lakes is flood-prone and hosts industrial and logistics activities whose operations are more vulnerable to climate risks, whereas similarly exposed areas to the west have less economic activity, meaning potential losses there would be lower.

Building resilience at all levels

Addressing the impacts of climate change effectively requires coordinated action between national, regional, and city-level policymakers. While national governments have the capacity to provide financial support when a disaster hits, de facto spreading risks across all regions of their national territory, sub-national levels typically have a more informed understanding of adaptation needs and can therefore help mitigate the exposure to and cost of climate-related disruptions.

Such an integrated coordination relies on granular information about the intersection of physical risk and economic activity. Such analysis not only reveals where climate impacts are likely to be most severe, but also highlights the need for targeted, local, adaptation and resilience planning.

In Europe, for example, where major city economies are, on average, more service-based and less industrial, adaptation efforts are increasingly focused on improving energy efficiency and liveability in a hotter climate. In contrast, many developing cities, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Lagos) and parts of South Asia, have more industrial-based economies and rapidly growing populations. Their adaptation strategies must therefore address infrastructure demand and development as well as the restructuring of economic activity away from carbon-intensive activity.

Managing the costs of a warmer world

Climate change is no longer a distant or abstract challenge—it is already reshaping the physical and economic landscapes on which growth and prosperity depend. The evidence is clear that warming is accelerating. As our analysis shows, even moderate temperature increases can translate into substantial and persistent GDP losses, especially if extreme weather events become more frequent and severe.

The task ahead is therefore not only to reduce emissions, but also to adapt to a climate that is already warmer and more volatile. Building resilience must become an integral part of economic and infrastructure development planning—from strengthening flood defences and climate-proofing infrastructure to redesigning energy systems and investing in nature-based solutions. For cities, which concentrate both people and economic activity, this means ensuring that adaptation measures go hand in hand with policies that support productivity and liveability.

As delegates convene in Belém for COP30, the message is clear: every fraction of a degree matters. The decisions made today will determine not only the pace of future warming, but also the economic resilience of the world we leave to the next generation.

What will these changes mean for you and your business?

The next phase of climate action will move from pledges to implementation, reshaping markets, investment flows and competitiveness. Businesses that anticipate these shifts and quantify their exposure will be best positioned to thrive through the transition.

At Oxford Economics, we help you assess the impact of mitigation policies across every facet of your business. Request a trial of our Climate Services and gain access to forecasts, scenarios and expert insight, along with our latest updates from COP30 today.

Tags:

Related Reports

Key take-aways from COP30

COP 30’s agenda had placed a strong emphasis on countries’ implementation of their emissions reduction target and, for the first time, several workstreams included discussions on unilateral trade policies.

Find Out More

Flooding risks diverge across UK cities, sectors and economies

Climate-linked flooding is becoming more severe, reshaping risks for UK cities, real estate, and local economies. Which areas face the greatest impact—and why?

Find Out More

COP 30 in focus: How to stay the course on the path to Net Zero

EMDEs are projected to account for 70% of global CO₂ emissions by 2050, making accelerated emissions reductions in these economies essential. Yet gaps in AE leadership—such as US policy rollbacks and insufficient climate finance—risk slowing the global transition.

Find Out More

Advanced economy leadership is key to the low-carbon transition

We modelled how advanced-economy leadership in innovation and finance could accelerate a global low-carbon transition.

Find Out More