Climate targets and a missed opportunity

A step in the right direction – 2035 emission targets published

Thanks to a flurry of reports released in September, Australia’s transition to net zero is now mapped out in unprecedented detail. The Federal Treasury’s Net Zero Modelling and Analysis Report, the Climate Change Authority’s 2035 Targets Advice Report, and CSIRO’s supporting modelling collectively chart a pathway that could deliver sustained growth consistent with greenhouse gas emissions falling by 62-70% below 2005 levels by 2035.

But these reports share a critical blind spot: they model the economy’s transition in isolation from the physical realities of a warming world. This is not a flaw in the research itself, but a result of the scope of research requested. This appears to be a missed opportunity to articulate the case for change, particularly given the release of the National Climate Risk Assessment underscoring that climate impacts are not a distant or abstract concern; they are a core economic driver, already shaping productivity, fiscal sustainability, corporate strategy, and regional resilience.

We risk viewing climate action purely through an investment lens, and not value insurance from climate peril

By omitting physical risk scenarios, the published suite of scenarios presents an overly optimistic picture of Australia’s long-term outlook. They show how growth might evolve under an orderly or disorderly transition – but not how the economy fares when heat, floods, droughts, or fires disrupt supply chains, damage infrastructure, or reduce agricultural output.

That omission matters for economic policy, corporate strategy, and household decisions alike. It also sets an artificially high bar for action. When the case for change is framed only around future prosperity, it invites a narrow investment test: we decarbonise only if it lowers costs or raises returns.

Viewed through that lens, climate action must pay for itself – we green the grid only if power becomes cheaper, buy electric vehicles only if transport costs fall, and decarbonise industries only if competitiveness improves. This framing misses the fundamental point: climate change poses an existential risk to Australia’s way of life. Mitigation is not merely an investment choice – it is an insurance policy against the risk of future systemic losses.

Quantifying physical risk

Assessing physical risk scenarios is complex but far from impossible. In fact, the Australian Government now requires major companies to do exactly this under the new Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards.

Traditional economic modelling of climate change uses “damage functions” – equations that link changes in temperature to shifts in economic output. Yet these functions often underestimate the true costs of climate change because they capture only average temperature increases, not the growing volatility and frequency of extreme events.

Newer approaches, including those developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and in Oxford Economics’ own work for the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s Insurance Climate Vulnerability Assessment, refine this methodology. By accounting for more frequent and severe extremes, they show how repeated physical shocks erode productivity, strain supply chains, and reduce economic capacity – leading to materially lower GDP outcomes in physical risk scenarios.

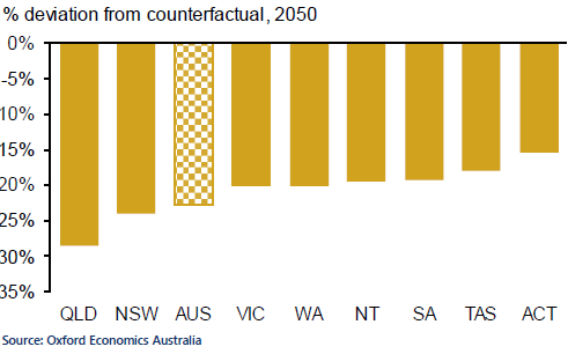

Specifically, in our research to inform the Insurance Climate Vulnerability Assessment we considered the economic impact of a scenario that assumes global warming reaches 2.5 °C by 2050 with an increasing frequency of extreme weather events representing a tail-risk view of physical risks. In this scenario, Australia’s economy is more than 20% smaller than the counter-factual scenario omitting all additional physical or transition risks.

Avoiding such a scenario is worth paying for.

Gross State Product, Current Policies Scenario

The real case for net zero

When the costs of physical damage are included, the economic rationale for early and decisive mitigation strengthens dramatically. The National Climate Risk Assessment identifies over a dozen nationally significant risks – including to water security, supply chains, and regional economies – each with measurable economic consequences.

Embedding these risks into future modelling would sharpen the case for action and help policymakers, investors, and communities understand the true financial value of resilience. Without this lens, Australia risks treating climate action as a discretionary cost rather than a core investment in national prosperity.

Australia’s transition to net zero is about more than energy and emissions. It is about safeguarding the economy and our way of life.

Related content

Common Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards (ASRS) pitfalls and how to avoid them

Blog Climate targets and a missed opportunity

Find Out More

Climate Risk Insurance Modelling for Australia’s Future

Explore climate risk insurance modelling to enhance sustainability and affordability in Australia’s insurance sector amid rising climate challenges.

Find Out More

Cities at the frontier of sustainability: insights from the Global Cities Index 2025 | Greenomics podcast

Explore insights from the Global Cities Index on city sustainability, key results and how governments can drive sustainable urban development.

Find Out More

What is the ‘hidden’ climate risk in your financial portfolio?

There is currently a gap in how the market understands and measures the extended climate risk that companies are exposed to via their interaction with the broader economy.

Find Out More

The Green Leap: Using regulation to combat deforestation

We exploring the European Union's bold initiative to tackle deforestation through the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

Find Out More

Key climate and sustainability themes for 2025

We expect economic growth to remain modest in 2025, although we don’t think a substantial slowdown is on the way either.

Find Out MoreTags: