Claims of deindustrialisation in Europe are overblown

- Our forecasts do not show any significant deindustrialisation over the next decades in Europe.

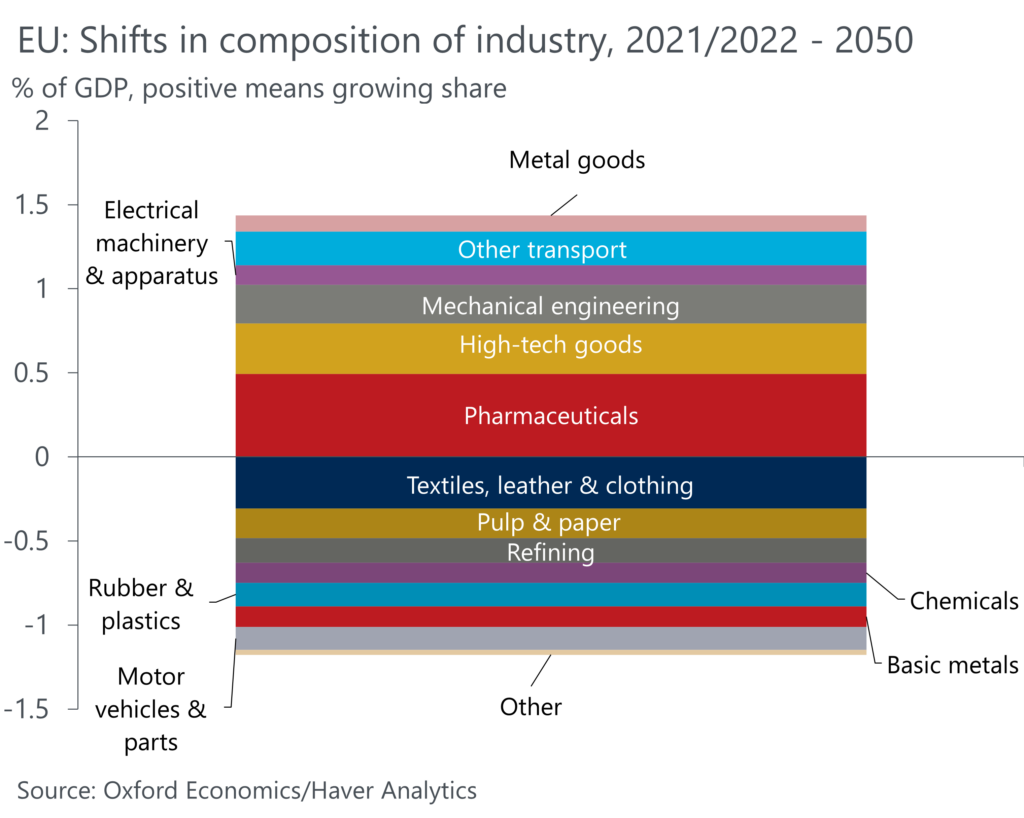

- However, Europe indeed faces substantial challenges that will impact low-skilled, upstream, energy-intensive and easily tradable sectors, causing them to shrink as a proportion of GDP and, in some cases, in absolute terms.

- High-knowledge, high-skill sectors like mechanical engineering, electronics, pharmaceuticals and electrical machinery will rise as a proportion of economic activity, offsetting declines in other industries.

In September 2022, at the high point of spiking European gas prices, Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo famously used the term “deindustrialisation” to describe what he feared would happen because of high gas prices. He warned that unless Europe acted, the continent faced the prospect of large-scale loss of manufacturing jobs and capability. Since then, this term has dominated discussions about the present and future of European industry.

At Oxford Economics, we think that these predictions around imminent or longer-term deindustrialisation are overblown.

Misconceptions about deindustrialisation

There are two uses of deindustrialisation that we think are flat-out wrong.

The first is as a description of the very real decline in industrial output in Europe, primarily Germany, over the past few quarters. While we do believe that there have been structural and cyclical headwinds contributing to the decline, it is more accurate to describe it as an industrial recession—something that happens periodically in any economy and is typically followed by a period of recovery. In fact, we believe the industry cycle is now turning for Europe, and we expect output levels to rebound by mid-2025.

Unlock exclusive economic and business insights—sign up for our newsletter today

The second wrong way to think about deindustrialisation is as a descriptor of Europe’s shrinking share and falling importance for global industrial output. This is undoubtedly real: we expect that eurozone industry will go from 12.2% of the global total in 2023 to just over 10% by 2050. However, this trend is more attributed to rapid economic growth in Asia, particularly China, rather than competitiveness issues in Europe.

Hover over the chart to check the value

So, what is the better way to define deindustrialisation? Our view is that the best measure of industrialisation in an economy is the share of GDP that such activities make up, particularly in larger and more complex economies. As such, deindustrialisation can be best understood as a drop in industrial output relative to the economy as a whole.

Using this definition, we can see that the industrial share of GDP moved very little in 2022/2023 relative to the past. Take Germany: manufacturing as a share of GDP has fallen to 22.2% as of Q1, which is only 0.26ppts lower than in Q1 2022 prior to the industrial recession. This is much less than in the last period of notable deindustrialisation, where the manufacturing share of economic output fell from 24.8% at the beginning of 1991 to 21.9% two years later—a fall of 2.9ppts that would be compounded by a further fall of 1.5ppts in the subsequent years. The mild decline we’ve seen in this latest industrial recession suggests that current industrial troubles should be seen within the context of a broadly weak economy, not necessarily an industry-specific problem.

The future of European industry

We do agree that European industry as a whole and specific industries are undergoing transformation; the difference is that we don’t think this will translate into deindustrialisation. Some industries will decline, but this will be offset by the rise of others.

Looking into the future, we believe Europe’s strengths lie in highly complex, specialised areas of manufacturing. These areas not only require a highly educated workforce, but also benefit from network effects, institutional knowledge, and the cumulative impact of decades of investment in intellectual property, patents and physical capital. There are also barriers to entry in terms of research costs and building up trust and reliability among potential customers.

Mechanical engineering, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and electrical machinery are examples of such sectors. Companies like ASML, the Dutch company that is crucial and unrivalled globally for producing cutting-edge machines that make the machines used elsewhere to produce semiconductors; Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical company behind the drug Ozempic; and Airbus, the transnational airplane producer exemplify the high-skill, high-specialisation sectors where Europe excels. These sectors have been growing as a share of total industry and economic activity.

While global competition in these areas exist, we see little sign that the European advantage is on the cusp of being overturned. Ironically, Europe’s struggles with an ageing workforce and labour shortages may prove to be an advantage, in the way that they incentivise a virtuous cycle of automation and the adoption of cutting-edge labour-saving technologies. Germany is, for example, currently a world leader in factory automation.

Industries at risk

While some sectors will still see opportunities, not all parts of European industry will thrive. There are in fact a number of sectors that we believe are poised for decline—in some cases terminal—over the next decades.

There are some commonalities shared across these declining sectors. They are, as a general rule, lower value-added, often produce goods that can be easily transported and traded, need low-skilled labour, and are often energy-intensive or otherwise reliant on fossil fuels.

The sectors facing most significant threats are:

Textiles & clothing

Forecast: decline. We see this sector falling from around 0.4% of GDP to just 0.1% by 2050.

Textiles production has been declining as a share of GDP and in absolute levels in Europe since the early 1990s. This labour-intensive industry has been decimated by the rise of fast fashion and the emergence of low-cost competitors, particularly in Asia. What remains in Europe tends to be more bespoke, higher-quality, and costly, which is a smaller market.

Pulp & paper

Forecast: decline. We see this sector falling from around 0.4% of GDP to 0.2% by 2050.

Pulp & paper has, in Europe and globally, been growing in line with broader industry recently, but we see a twofold challenge ahead. First, global demand is expected to plateau as the world becomes more digital. Second, Europe will capture a smaller share of this stagnating market. The sector’s energy-intensive production will face mounting pressures from rising energy costs and growing sustainability concerns. Policies like the carbon border adjustment tax can only partially mitigate these issues.

Refining

Forecast: decline. We see this sector falling from around 0.4% of GDP to 0.3% by 2050.

Rubber & plastics, basic metals

Forecast: stagnation. We see this sector falling from around 0.8% of GDP to 0.7% by 2050.

Both sectors face a similar challenge with sustainability and reliance on fossil fuels on a continent that is increasingly pushing in the opposite direction.

Chemicals

Forecast: slight growth. We see this sector falling from around 1.2% of GDP to 1.1% by 2050.

Chemicals faces a mix of competitive and environmental pressures. Much of this production is expected to continue for decades and, in some cases, be retrofitted for more eco-friendly production processes. However, these efforts primarily aim to protect existing production capacity and production levels, rather than setting the stage for new investment and growth.

Download the full report, 'The future of industrial activity in Europe'

Our forecasts do not show any significant deindustrialisation over the next decades in Europe—in fact, we find predictions around imminent or longer-term deindustrialisation to be overblown.

The analysis forecasts in this blog are backed by our Global Industry Service, which provides forecasts and insights for over 100 sectors in 77 countries. To unlock the power of these industry insights for your business, request a free trial by clicking here.

Tags:

Related Reports

Trump tariff turbulence threatens global industrial landscape

Europe’s defence splurge will help industry – but by how much?

Blanket tariffs from Trump drag down industrial prospects | Industry Forecast Highlights