Blog | 03 Jun 2021

This economic recovery is different, but why?

The economic fallout from the pandemic has thrown economists a number of curve balls. The usual rules about recessions, with business investment falling sharply and personal consumption holding relatively steady, have been overturned. In countries such as Australia, New Zealand and China that have been able to keep COVID-19 at bay and sustainably re-open (a clear pre-requisite for a lasting recovery), the return to economic normality has also thrown up some surprises—the rebound has been remarkably strong, with pre-COVID levels of employment and GDP reached within a year of the initial lockdowns.

So what has made this time different from ‘traditional’ recessions? Using Australia and NZ as case studies for where the recovery is well-entrenched, it can partly be explained by the amount of fiscal and monetary support that the authorities have supplied. Budget deficits have increased sharply, and central banks have pulled all of their monetary levers. Under normal conditions this amount of support would generate a substantial amount of additional activity in the economy, particularly with much of it frontloaded given the focus on direct transfers to households and businesses.

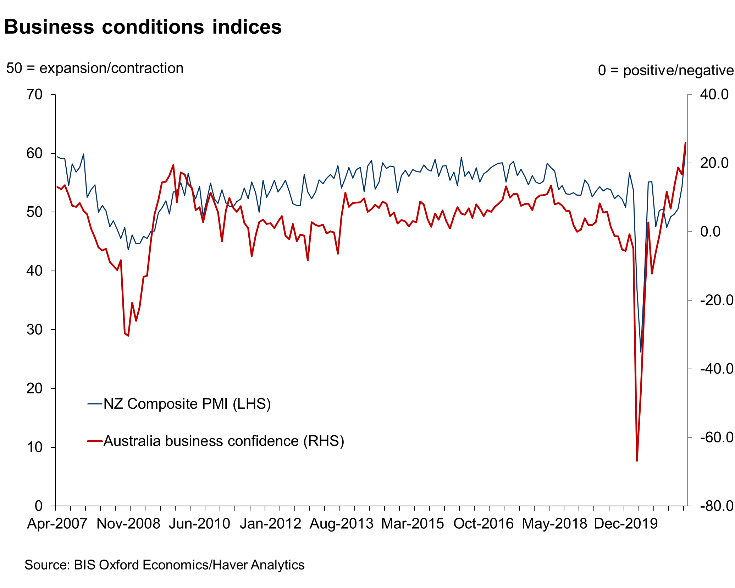

But the policy response can’t fully explain the speed and timing of the rebound. The high frequency indicators and confidence surveys in Australia and New Zealand troughed in April/May 2020, months before the majority of the fiscal supports hit the economy.

Part of the rapid rebound can be explained by the uniqueness of the situation. Forcing parts of the economy to close and then allowing them to re-open has resulted in the release of pent-up demand; McDonald’s, for example, reported that the week after New Zealand’s lockdown ended was one of its busiest on record. But this isn’t a complete explanation either. Localised (and short) lockdowns aside, day-to-day life in both countries had largely returned to normal by the end of 2020. But spending on services such as dining, travel and entertainment is only now returning to pre-COVID levels.

Part of the rapid rebound can be explained by the uniqueness of the situation. Forcing parts of the economy to close and then allowing them to re-open has resulted in the release of pent-up demand; McDonald’s, for example, reported that the week after New Zealand’s lockdown ended was one of its busiest on record. But this isn’t a complete explanation either. Localised (and short) lockdowns aside, day-to-day life in both countries had largely returned to normal by the end of 2020. But spending on services such as dining, travel and entertainment is only now returning to pre-COVID levels.

Looking again at the confidence surveys and anecdotal reports, the fiscal policy response appears to have had an additional, crucial role in the initial recovery. It provided businesses and households with certainty over their financial position for a number of months by guaranteeing at least a part of workers’ wages and businesses’ cash flow; in Australia the wage subsidy scheme ran for six months initially (and was ultimately extended to twelve months for eligible firms), while in NZ it ran for three months with a commitment to renew it if required. By providing some clarity in a time of extreme uncertainty, firms and individuals felt confident enough to at least partially maintain their spending levels, which in turn supported activity and jobs.

The economic dividend from the aggressive policy response is also likely to extend beyond the initial recovery phase. The short, sharp nature of the downturn in both countries has limited the decline in business confidence and investment and the development of negative labour market hysteresis (scarring) effects on both countries’ productive potential; the rise in long-term unemployment will be relatively small, considering the size of the economic shock. And by adding additional funding for government investment into the mix, this should mean that in the long run, both economies are able to return to their pre-COVID trend profile for living standards.

This experience suggests that once high vaccination rates enable a sustained relaxation of restrictions in other countries, the rebound in economic activity will be rapid. Furthermore, all other things equal, the top-performing economies are likely to be those that have used fiscal policy to limit the damage in the labour market and business investment; if this is added to thorough investment in infrastructure and other productive capital, some countries could well sustainably lift their trend growth profile.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

US Key Themes 2026: Exceptionalism amid fragmentation

US exceptionalism is alive and well, and that won't change in 2026.

Find Out More

Post

Global Key themes 2026: Bullish on US despite AI bubble fears

We anticipate another year of broadly steady and unexceptional global GDP growth, but with some more interesting stories running below the surface.

Find Out More

Post

Industry key themes 2026: Industry will grow if you know where to look

Prospects appear solid for global industry in 2026, but activity is set to remain regionally and sectorally divergent.

Find Out More