Why have China’s exports held up so well under higher US tariffs?

China’s exports have adapted, rather than retreated, under higher US tariffs.

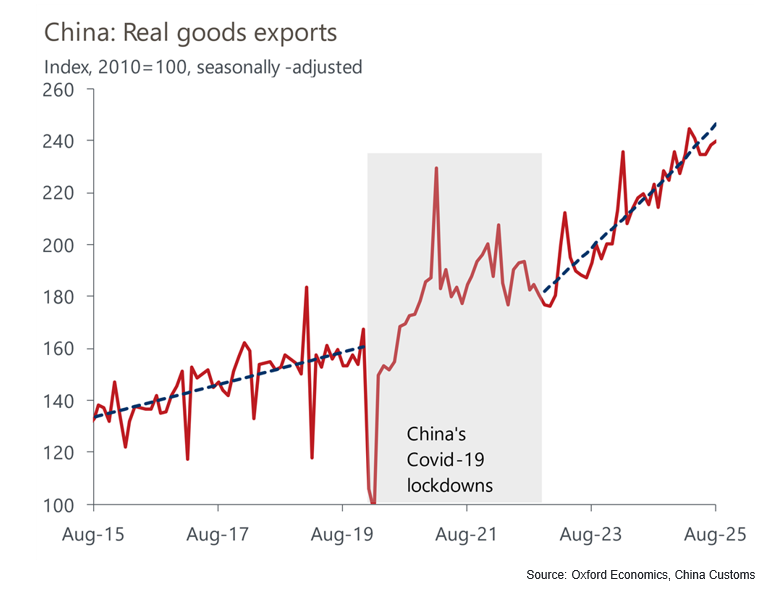

Despite significant US tariff uncertainties, China’s exports have held up much better than most market analysts had expected this year. We recently raised our 2026 forecast for China’s real goods exports growth to be broadly flat, following an anticipated 8.3% expansion this year. By contrast, we project US exports will decline by 3.4% in 2026.

Resilience beyond frontloading

While much of Asia benefited from export frontloading activity through to July, our own detrending analyses suggest similar frontloading activity for Chinese goods, including those shipped directly to the US and those rerouted or assembled elsewhere first, started in December last year and only lasted until April. Shipments were notably around 7% above trend-implied levels in December, prior to US President Donald Trump’s inauguration, and 9% higher in March, ahead of the announcement of higher tariffs in April.

Unlock exclusive economic and business insights—sign up for our newsletter today

The relatively small boost to China’s recent export activity from order frontloading implies that its export resilience has been driven by other factors that also explain a stronger growth path since the end of 2022.

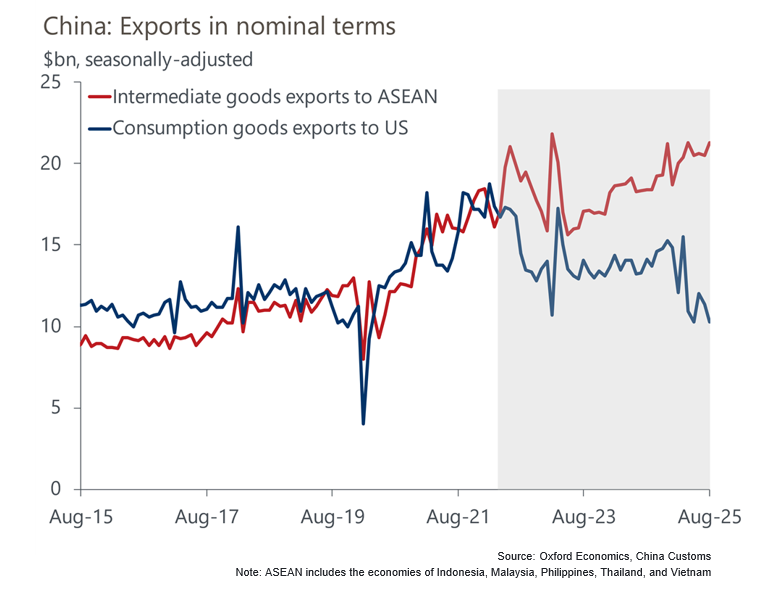

Cyclically, stronger trade diversion has supported China’s exports. The US tariff gap between China and the rest of Asia is now far above the 4%–5% average industrial profit margin of Chinese firms, which has encouraged rerouting of trade via ASEAN. We estimate about US$77bn in Chinese goods bound for the US have been redirected through ASEAN since April.

Structurally, China’s export base has also evolved by shifting toward higher-value sectors, underpinned by an aggressive industrial push since late 2022, amid significant domestic headwinds. This has made China’s exports far more resilient to unilateral US tariffs.

China’s export transition strategy 1: Diversifying from developed to emerging markets

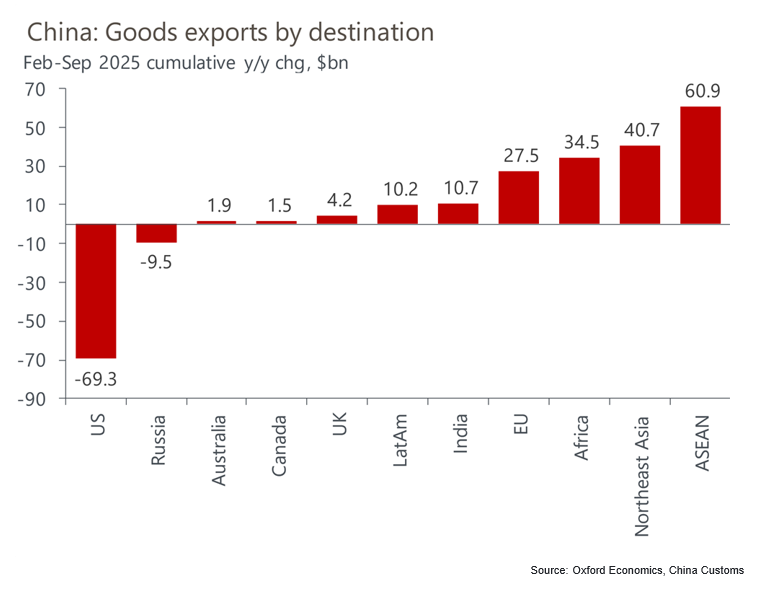

The reweighting of Chinese exports away from developed markets (DMs) toward emerging markets (EMs) has been underway since the 2018 US-China trade war. ASEAN, Latin America, and Africa now account for a steadily rising share of China’s outbound shipments, offsetting softness in developed markets in the US and Northeast Asia. In particular, exports of vehicles, communication equipment, and electrical machinery to EMs, such as those in ASEAN and Latin America, have risen sharply due to both supply chain diversification and rising local demand for China’s electric vehicles.

To be sure, the US and Northeast Asia still represent about 32% of China’s total export value (versus 45% in 2017), but their dominance is fading. The decline in exports to Japan and Korea stems from a mix of external frictions and domestic upgrading. On the one hand, initiatives such as the Chip 4 alliance have reduced Korea’s reliance on Chinese inputs in high-tech sectors. On the other, China’s movement up the value chain has naturally displaced its own low-margin exports of textiles, garments, and foodstuffs to regional peers.

This year’s tariff increases have reinforced these redirections. Since February, export growth to ASEAN, India, Africa, and Latin America has been nearly double the pace of contraction in direct shipments to the US, suggesting that new trade links are gaining traction faster than older ones are eroding.

However, deeper exposure to EMs also brings new vulnerabilities. An analysis of 87 key trading partners shows that 61 now run bilateral trade deficits with China, and 40 have seen these deficits widen relative to their foreign reserve holdings since 2017. Many of these bilateral trade imbalances have persisted over the past decade, especially in low-income economies across Asia, Africa, and EMEA. So, while stronger demand from these markets supports near-term export momentum, it also raises China’s sensitivity to the financial fragilities and demand cycles of economies less equipped to sustain prolonged import growth.

China’s export transition strategy 2: Towards intermediate and capital goods

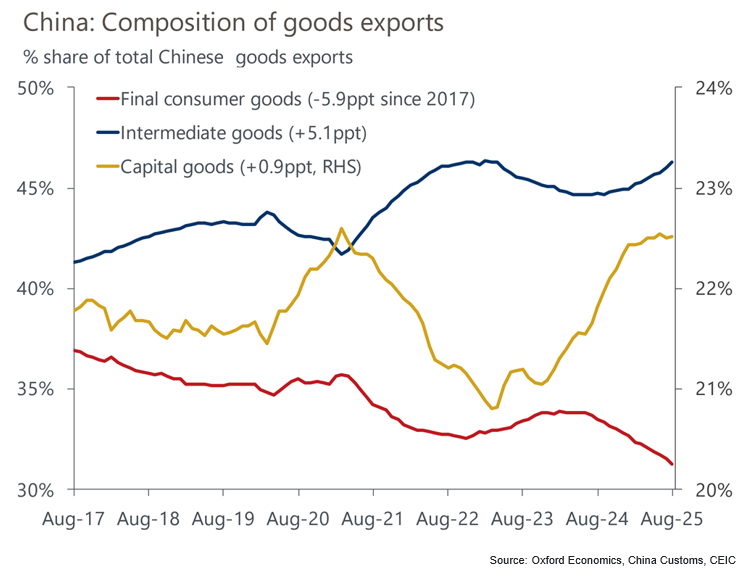

In the 2020’s, Chinese manufacturers were predominantly a “final assembler” of product parts. Now, Chinese manufacturers are shifting towards being a key supplier of intermediate inputs across many product supply chains.

Since the mid-2010s, other economies have become increasingly reliant on Chinese-made inputs, especially in green industries such as solar photovoltaics. OECD data show China’s value-added contribution to global final demand reached 17% of global GDP by 2022, up 2.3ppt since 2017. This corroborates with China’s customs data, which show nearly half of China’s total exports are now considered intermediate goods.

The implications of China’s multi-year pivot from final consumer goods to capital and intermediate goods means that it is increasingly difficult for global manufacturers to exclude Chinese components or play down their Chinese affiliation in supply chains. An entrenched presence in upstream production stages also makes demand for Chinese inputs relatively inelastic to tariff shifts.

China’s export transition strategy 3: Moving up the value chain

China’s drive for greater self-sufficiency has been central in its shift toward higher value-added manufacturing and exports. High-tech goods – including computers, telecommunications equipment, aerospace products, and biotechnology – now account for around 30% of total exports, or roughly US$920bn, while electromechanical products exceed 55%. This composition underscores a deliberate policy emphasis on innovation-led competitiveness. Notably, exports in these segments have continued to expand despite successive rounds of US tariffs.

Critically, China’s comparative advantage lies in its capacity to produce high-value goods at a low structural cost. Large-scale production, dense supplier networks, and productivity gains from automation and robotics have reinforced its manufacturing edge. Although slim profit margins may not be sustainable over time, any price normalisation is likely to be gradual. Recent policy signals, including the government’s “anti-involution” initiative, appear to be aimed less at easing competition and more at improving efficiency and technological self-reliance, which should further consolidate China’s competitiveness in high-value manufacturing.

Building out its own indigenous vertical supply chains for high value-adding products also means that China’s importsfor processing trade or other special re-export arrangements have declined steadily from 50% in 2005 to below 30% of China’s imports as of 2024. Put another way, China has been reducing imports of intermediate goods, notably chemical materials, automobile parts, and electronic components. Meanwhile, China’s been increasing its imports of final consumer goods, particularly from ASEAN economies.

Policy implications of China’s export resilience

China’s contribution to global trade has become increasingly one-sided. Over the past two decades, its exports have continued to capture market share, while its share of global imports has remained broadly stable at around 9%. Strengthening domestic supply chains has reduced reliance on foreign inputs, reinforcing this asymmetry.

A key enabler has been the renminbi’s real depreciation, which has sustained price competitiveness even amid weak domestic inflation. By some market estimates, the renminbi remains more than 20% undervalued in real terms.

However, this export-led resilience comes with trade-offs. Continued dependence on external demand delays macro rebalancing efforts towards consumption-led growth. While political support for boosting household spending is clear, constraints related to financial stability, fiscal prudence, and moral hazard limit the scope for large-scale stimulus. For now, exports continue to carry much of the growth burden, effectively meaning that Chinese households are subsidising global consumers through high savings and restrained prices.

Across Asia, the spillovers of China’s export transitions are mixed, which we will explore in greater detail in a later note. China’s manufacturing strength could crowd out regional competitors, echoing aspects of the early 2000s “China shock” that saw US manufacturing employment fall by about 25%. Yet the disinflationary effects of abundant, low-cost Chinese goods are also supporting real incomes and giving central banks room to ease policy amid slowing industrial momentum.

Tags:

Related Reports

China and AI underpin stronger global trade outlook

Global trade is set for a stronger-than-expected rebound, supported by lower US tariffs, continued AI-driven investment, and China’s renewed export push. Our latest forecasts show upgrades to both nominal and volume trade growth in 2025–26, even as legal uncertainty surrounding US tariff mechanisms and evolving geopolitical dynamics pose risks to the outlook.

Find Out More

China’s Outbound Recovery: Slowing but Still Rising

Research Briefing Why have China’s exports held up so well under higher US tariffs? The rebound continues, but slowing demand, economic headwinds, and shifting traveler preferences are reshaping the outlook.

Find Out More

Navigating fundamental drags and policy drives for China’s manufacturing investment in 2026

Chinese manufacturing fixed investment shrank by 6.7% year-on-year in October, deepening the slump that began in July. We expect this decline to continue for most of H1 2026. The pace of recovery will depend on the policy support in the Fifteenth Five-Year Plan.

Find Out More

Tariffs take a toll despite easing trade hostilities

Global tradeflows remain under pressure despite easing tariff tensions. Recent US–China agreements reduce select import taxes and support China’s 2026 outlook, yet US imports continue to fall and supply chains pivot toward Asia and Europe. Containerised trade is set to expand, while bulk shipments soften alongside weaker industrial demand.

Find Out More