Booms, busts and bulk water – a familiar infrastructure challenge is unfolding now

Booms, busts and bulk water – a familiar infrastructure challenge is unfolding now

Australia last experienced a boom in water-related infrastructure construction in the 2000s and early 2010s, following two decades of underinvestment in the 1980s and 1990s. Now, around 15 years later, another tremendous wave of investment is planned – but the sector faces critical skills and cost challenges if this investment is to be realised.

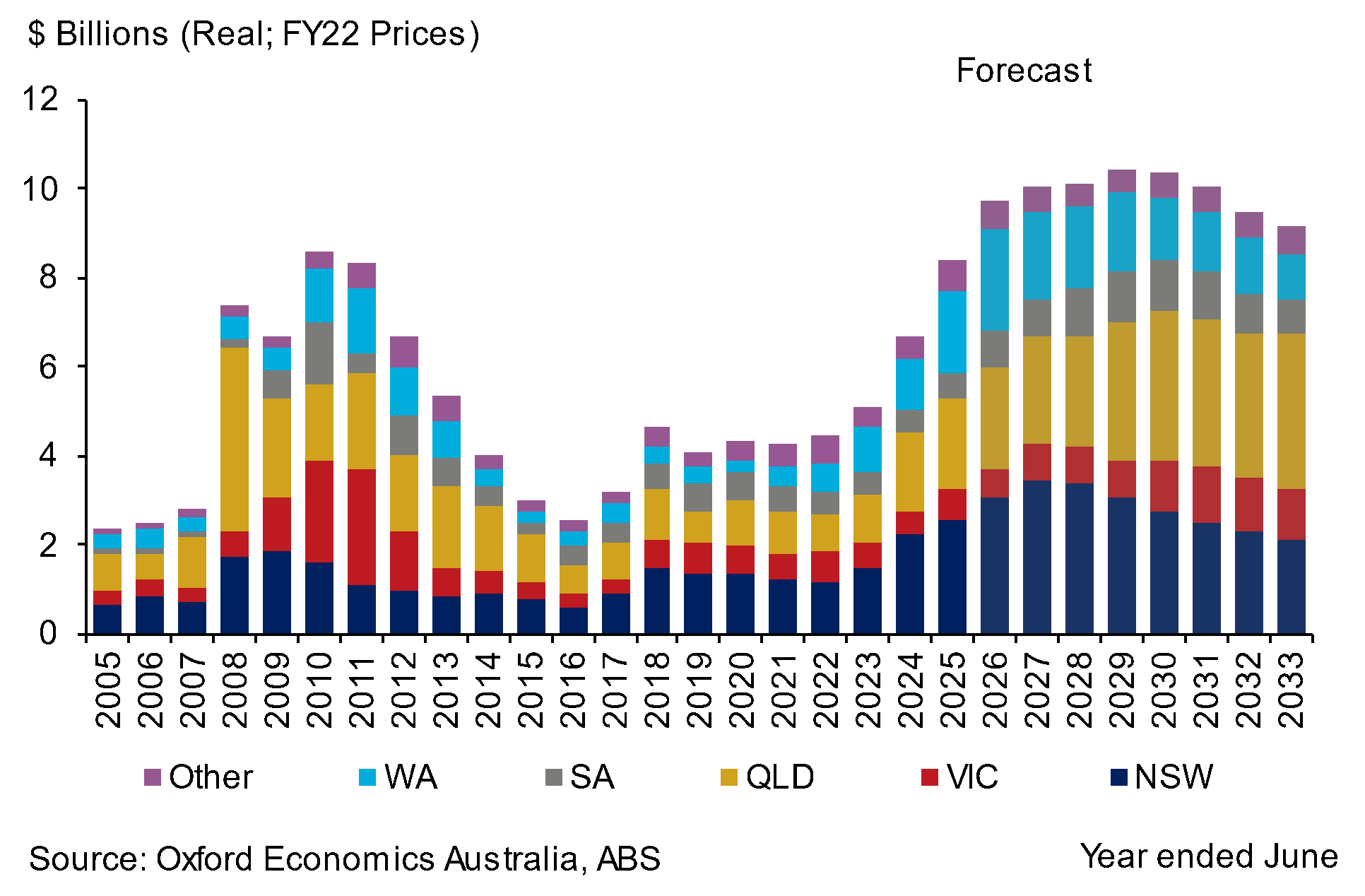

For all the current talk of the new investment growth drivers in the economy – AI and data centres, clean energy transition, net zero manufacturing using hydrogen, new housing, health infrastructure and defence – very little has been written about something far more fundamental, which is a necessary ingredient for nearly all of the above: water. (Well, apart from this Research Briefing by our own construction forecasting team, which was published this week, and the key chart showing cycles in water investment is shown in Figure 1 below.)

Figure 1: Water Supply and Storage Work Done, $Billions, Australia, 2022-23 Prices

Australia is the driest inhabited continent (sorry, Antarctica!) in the world, with over 70% of its land classified as arid or semi-arid due to low rainfall. The availability of a reliable water supply is a critical determinant of where Australia’s population and industry are located. In a land of “droughts and flooding rains”, the development of large bulk water infrastructure – including dams, reservoirs and pipelines – has been critical for the development of Australia’s regions, cities and our primary and secondary industrial base.

Water infrastructure booms and busts have littered Australia’s infrastructure history

Australia, mirroring global trends, experienced a ‘golden age’ in dam building during the post-war period from the late 1940s through the 1970s. The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme (1949–1974) – with 16 major dams, 7 power stations, and 225 km of tunnels and aqueducts – symbolised Australia’s success in both nation-building and post-war immigration. Warragamba Dam (then the world’s fourth-largest domestic water supply dam) was completed in 1960 to secure Sydney’s growth. Other major dams, including Eildon (1955, Victoria), Keepit (1960, NSW), Dartmouth (1979, Victoria), and Fairbairn (1972, Queensland), along with many irrigation storages across the Murray–Darling Basin, were also built during this period.

However, during the 1980s and 1990s, major bulk water infrastructure development slowed, with the focus shifting away from dam megaprojects to better demand management, water markets, and efficiency measures. Antipathy to new dam projects from the emerging environmental movement in the 1970s and 1980s also contributed; the proposed Franklin River Dam in Tasmania was one of the defining issues in the 1983 Federal election that brought Bob Hawke’s Labour Party (which opposed the dam) to power.

The Millennium drought brought another wave of bulk water investment

After trending down for two decades, water storage and supply construction reached very low levels in the late 1990s, leaving key infrastructure in some states in urgent need of upgrades. From 2002/03, water construction activity began to edge higher again. Work done rose around 90 per cent between 2002/03 to 2006/07, peaking at $2.8 billion, before a tremendous surge in works took place in 2007/08, with activity more than doubling to $7.4 billion and then exceeding $8 billion in both 2009/10 and 2010/11(all values in constant 2022/23 prices).

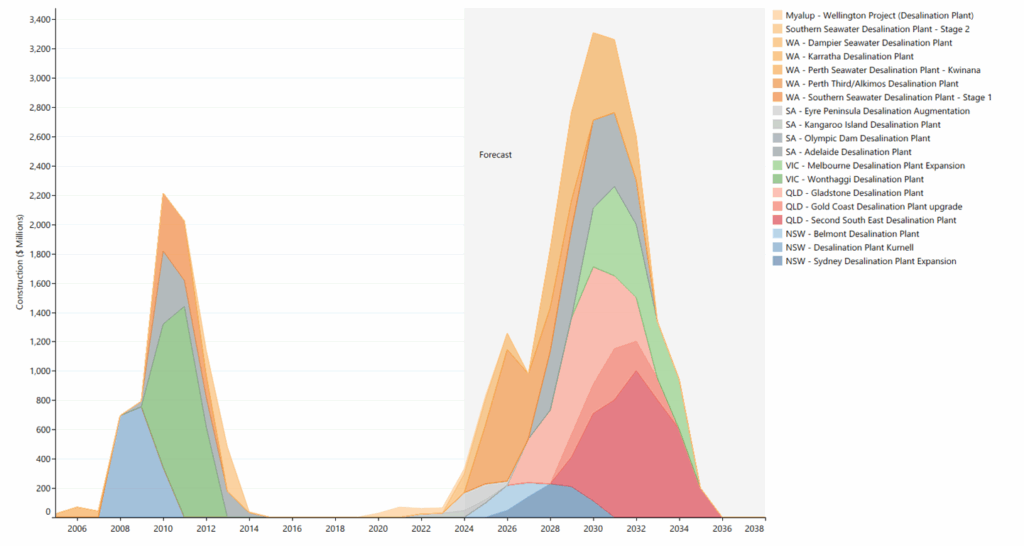

The need to upgrade ageing infrastructure and countering the effects of the prolonged Millennium Drought (1997-2010) were key catalysts of the 2000s water infrastructure boom. Water insecurity reigned as dam levels fell precipitously across the country. Desalination plants were built in nearly every major mainland capital city, including two in Perth (commissioned 2006 and 2011), Gold Coast (2009), Sydney (2010), Adelaide (2011), and Wonthaggi near Melbourne (2012). Queensland also invested billions in today’s dollars on the Western Corridor Recycled Water Scheme and the SEQ Water Grid, comprising major interconnecting pipelines. South Australia also invested in the North-South Interconnection System in Adelaide, while new dams were built in Queensland (Wyaralong, completed 2011) and the ACT (the enlarged Cotter Dam, 2013).

But few large projects have been completed since, creating a skills challenge…

Australia’s strong skills base in dam engineering was established during the post-war ‘golden age’ of dam investment and sustained somewhat through the subsequent Millennium Drought investment cycle. However, as Australia embarked on a series of new engineering investment booms in the 2010s and 2020s – across roads, rail, mining and energy, particularly – very little major project work (outside of Snowy Hydro 2.0) continued in the water sector. Cotter Dam remains the last big dam built in Australia, and that was well over a decade ago.

Combined with the rationalisation and corporatisation of water authorities in the 1990s and 2000s, an ageing skills base, and relatively little focus on dam engineering in undergraduate degrees (and perhaps also a general lack of awareness of dam engineering careers), the result has been an exodus of engineering skills away from the bulk water industry.

…given the large plans ahead for a new wave of water infrastructure

Unfortunately, this leaves Australia dangerously exposed to further critical skills shortages as the next wave of infrastructure investment unfolds. If left unaddressed, this will result in further project delays, failures and unnecessarily strong cost escalation at the project level. At a broader level, it may well impact our ability to hit key policy targets for energy, housing and net-zero manufacturing over this decade and next.

Figure 2: Desalination Work Done by Project, $Billions, Australia, 2022-23 Prices

It is not just bulk water dams which in the firing line – rather a whole swathe of investment is at risk without adequate investment in bulk water supplies or dam infrastructure. It turns out that Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Mariner was right – there is water, water everywhere!

And some of it will definitely be to drink! But we increasingly need more water, not just for water security for growing populations and for agriculture, but to underpin new data and energy technologies. While data centres are known to be highly energy-intensive, their cooling requirements are also very thirsty on water – and we are already in the midst of a data centre building boom in Australia to meet existing cloud computing demands, let alone the next wave of AI data centre development.

The green transition of the national energy market is also reliant on establishing new storage capacity from pumped hydro schemes as well as batteries. Manufacturing hydrogen as a potential future green energy source for steel or cement manufacturing itself requires large volumes of water, which will depend on investment in new desalination plants. Mining the critical minerals to support the new economy will also invariably mean building and maintaining more tailings dams.

Even meeting future housing targets will critically depend on having more bulk water capacity and the distribution networks to service greenfield developments and brownfield densification. And on top of this, climate change is making rainfall patterns more volatile, meaning we need a wider range of water assets across our regions and in our cities rather than one big dam to meet all our needs.

Implications

So what does all this mean?

For policymakers, it means recognising that meeting important policy goals across housing, energy, data, net zero, and manufacturing will require an enormous investment in our bulk water infrastructure. Much as governments have realised that building houses requires investment in enabling civil infrastructure like roads and utilities, a coordinated, achievable plan for water infrastructure is also necessary to meet our broader policy goals. Ideally, these plans should not be boom-bust like our experience but result in steadily growing levels of work, which can best foster a sustainable recovery in industry capability.

For the water industry, it means facing the challenge of re-growing its skills base to meet the demand challenge. More work needs to be done to quantify how many more people we will need, by occupation and region. But we have been here before. These challenges are very similar to those experienced in the rail and roads industries in recent times, which had to quickly redevelop and grow a highly skilled workforce to deliver a suite of infrastructure across Australia over the past decade. Older professionals have vital skills which the water industry will need to retain. Strong global demand may limit the skills we can attract from overseas. Skilled professionals in other segments (roads, rail, mining) may need to be recruited. Rising numbers of new graduates will need to be inducted – ideally helped by the prospects of a strong, long-term pipeline of projects and hence ongoing career development. Interestingly, increasing the graduate intake may also mean changing negative environmental perceptions about dam engineering. Unlike the Franklin controversy, pumped hydro dams may now be seen as a necessary part of meeting Australia’s emissions targets.

For all stakeholders – including the construction industry and project owners, it will mean acknowledging rising risks in project development, timing and delivery – and ultimately construction costs. While water infrastructure construction is on the rise, it will still be competing heavily for skills and materials from other sectors, and this competition will heat up later this decade as other, currently latent sectors, also recover alongside housing investment and a warming economy. Capacity constraints are unlikely to leave us, productivity gains may yet prove elusive, and there will remain the risk of further geopolitical events which can impact global supply chains and access to international skills.

These risks point to the need for more collaborative, rather than adversarial, approaches in how projects are developed, procured and delivered, and doing more work to quantify what the risks mean for skills and materials shortages and construction costs.

This is, literally, what we at Oxford Economics Australia have been helping our clients do for decades in roads, rail, energy, mining, telecommunications, and building, both in Australia and overseas. I remember well the desalination boom during the Millennium Drought, visiting the teams of engineers working on design, and the work we did forecasting demands, capacity risks, costs and escalation. (I also remember it raining a lot after each plant was built!)

Another wave of water investment is already well underway – and has a lot longer to run.

Related content

Australian Real Estate Consulting

Clarifying the economic real estate market conditions to enable more effective strategic decisions.

Find Out More

The Construction Productivity Challenge in Australia

Delve into the state of construction productivity in Australia. Understand the factors affecting growth and how innovation can transform the industry for the better.

Find Out More

5 Key Strategies for Productivity Growth in Australia

Australia’s productivity has stagnated due to weak business investment, declining dynamism, slower technological payoffs, and a meek appetite for economic reform.

Find Out More

Growth in Australia’s Build-to-Rent sector for FY2025

The build-to-rent sector is back in growth mode, with unit starts rising 24% in FY2025, a strong pipeline ahead, and key transactions driving momentum.

Find Out More

Australia’s business investment outlook for FY26

Business spending in Australia rose modestly in Q2, but investment expectations for FY26 remain subdued.

Find Out More

Office rents entering growth cycle in Australia

CBD office markets in Australia face high vacancy rates, but a supply shortage is expected to drive a strong rent recovery. Effective rents are forecast to rise sharply up to 108% in some cities by FY2035 as vacancy rates fall and incentives normalise.

Find Out More

Queensland Budget maintains sizeable pipeline of work in Australia

Explore the 2025/26 Queensland Budget, focusing on public infrastructure, housing support for first home buyers, and key projects for the 2032 Brisbane Olympics.

Find Out More

Understanding Australia’s Goods Trade Dynamics in 2025

Explore Australia's goods trade dynamics, with rising exports and falling imports. Learn how global demand impacts the trade balance and future projections.

Find Out More

Unpacking Australia’s dwindling productivity growth

After years of labour productivity stagnation, leaders are calling for urgent action to revive Australia productivity growth. The upcoming national productivity roundtable represents a critical opportunity to address long-term challenges and develop actionable reforms.

Find Out MoreTags: