Ageing Japan needs a drastic shift in migration policy

We believe the huge increase in foreign workers in Japan will prove unsustainable, despite the considerable labour shortages across various sectors, caused by unfavourable demographics. As shown by the far right’s progress at the recent election, Japan isn’t ready to drastically transform policy and society to accommodate large numbers of foreign workers as full citizens, rather than as ‘guest workers’.

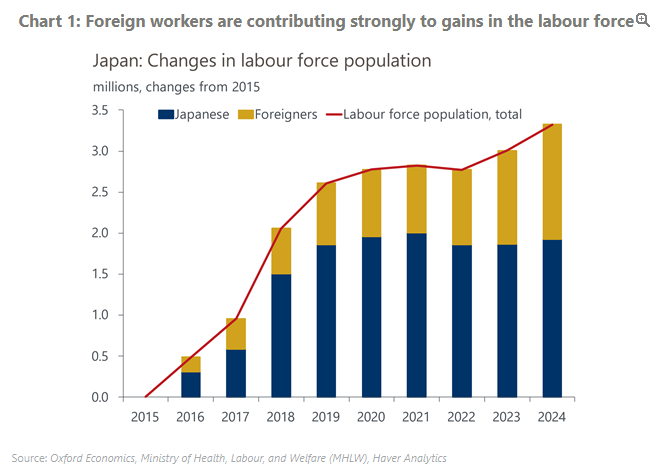

In 2024, over 340,000 foreign workers entered Japan, twice the pace the UN and the government had forecast, and nearing levels seen in Canada and the UK – countries more traditionally associated with immigration. Many foreign workers arrive with duration- and occupation-limited visas, and typically engage in low-paid manual labour. Manufacturers, in-person services, and the construction sector are increasingly reliant on foreign workers for labour.

In our Global Economic Model, we assume Japan’s inflow of foreign workers will be around 150,000 per year over the next couple of decades, based on the UN’s World Population Prospects, which is similar to the government’s baseline assumption. At this pace of immigration, Japan’s working-age population will shrink by 8% by 2035 and 15% by 2045, as it won’t be enough to offset the decline in the domestic working-age population.

If Japan were to accept 500,000 people per year, though, the working-age population would stabilise in the 2040s. However, the ratio of foreigners in the population would surge sharply from the current 3% to 30% by 2060 in this scenario. Given the political landscape and recent electoral gains for nationalist politicians, as well as the currently meagre opportunities for holders of working visas to obtain citizenship and the benefits available to Japanese people, this solution to Japan’s labour shortages seems highly unrealistic.