UK university crises will hurt UK cities

The UK’s higher education sector faces a financial crisis

On A-level results day this year, a record number of school leavers were accepted into their first choice of university. This is a symptom of the current higher education climate in the UK, where stagnant fees, increasing restrictions on international students, reduced research funding, and higher costs are putting universities in increasing competition with one another for more domestic students, and crucially, the fees these students pay. Universities founded post-1992, many of which were previously polytechnics, are especially exposed.

In the meantime, some are searching for new ways to manage financial strain. Most recently, news broke that the Universities of Kent and Greenwich are set to merge into the UK’s first “super-university”, a potential blueprint for other institutions navigating the crisis.

UK universities play a crucial role in UK cities economies

Universities are not just centres of learning, they are engines of local growth. Given the important role universities play in local and regional economies, their poor financial position will have implications for local economic performance.

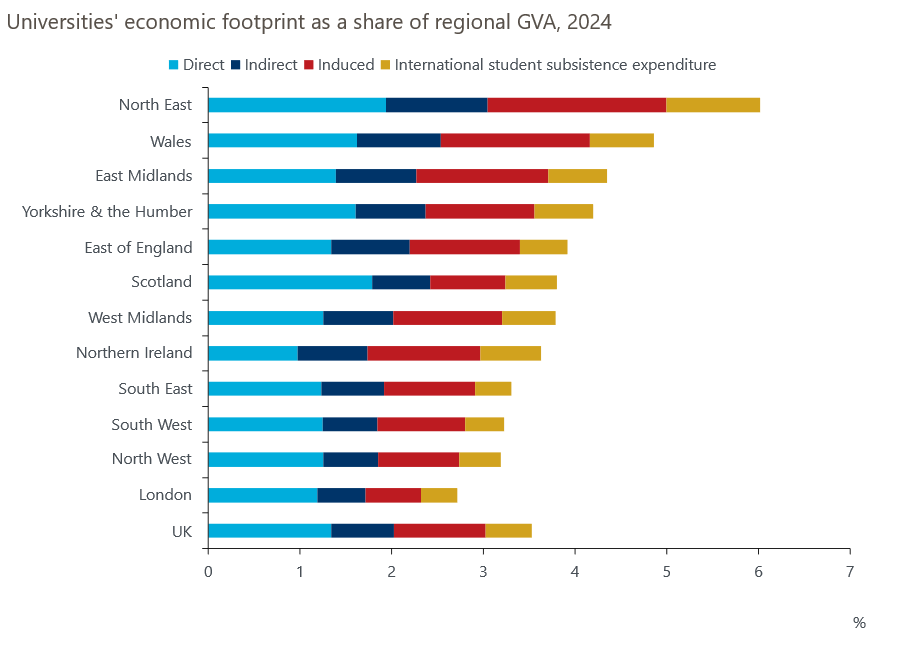

To understand which parts of the UK might be most affected by the difficulties in the higher education sector, we quantified the current economic footprint of 166 UK universities and higher education institutions using the Oxford Economics Local Economic Impact Model and publicly available data from the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA) and an input-output framework.

Unlock exclusive climate and business insights—sign up for our newsletter today

SubscribeOxford Economics Local Economic Impact Model quantifies the economic impact of the universities’ direct activities, as well as the impact created by their supply chain spending (indirect impact), the impact created by wage spending (induced impact), and the impact of international students’ subsistence spending. The model calculates the employment and gross value added (GVA) impact of each institution on each local authority in the UK, taking into account the local conditions of the economy. Our modelling approach is set out in detail in our recent work for the University of Bristol and the University of Bath.

Overall, the footprint of universities supported 1.2 million jobs in the UK in 2024. London and university towns see the greatest absolute benefit with 188,000 jobs supported in London and 155,000 jobs in the South East. Outside of these regions, it is mainly the larger UK cities that see a significant impact from university activities, including Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham, as well as university towns such as Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham.

Economies of the North East, East Midlands, Yorkshire & the Humber, and the devolved nations are most dependent on universities

By comparing the economic footprint of universities to the size of regional economies we find that diversified and high-income economies are less directly reliant on the university sector for economic output. In fact, weaker regional economies, particularly the North East and Wales, are the most dependent, with the economic footprint of universities accounting for 6.0% and 4.9% of total GVA, respectively, compared to 3.5% for the UK as a whole. This means that issues in the university sector are likely to carry outsized risks for the UK’s least resilient places.

A substantial portion of the economic footprint of universities in local areas is underpinned by the spending of international students, as well as the spending of wages of university and supply chain employees. This spending primarily supports the “everyday economy,” which includes sectors where households tend to spend their income, for example hospitality and retail. The everyday economy is not the most productive nor fastest-growing sector of the economy, but it provides substantial employment opportunities and is the main driver of growth in many areas.

A struggling higher education system can be an opportunity for reform

In the 2026 QS World University Rankings, 17 UK universities placed in the top 100. Comparatively, France and Germany placed nine between them. The high quality of universities in the UK is one of the economy’s greatest assets, and it is one of the reasons why London ranks as having the best human capital of any city in the world in our Global Cities Index. If the university sector is struggling, this is a problem for the UK economy—including the weaker-growing regions of the UK that are more reliant on the footprint of universities. And as these weaker regions depend more on the university sector, a future decline in the scale of universities operations could increase regional inequality. In a university-reliant local authority economy, a university going bankrupt would have a substantial negative impact that would reverberate through the whole area. It is therefore difficult to overstate the value of universities to the UK’s economic model, both at the national and the local levels.

Yet with challenges come opportunities, and the risks the UK’s higher education system faces could spark a rethink in how the UK funds, supports, and provides education. Central to this is an endemic skills problem, with substantial numbers of people both under- and over-employed, and too few people getting the intermediate skills the economy needs. Also, with the onset of AI, automation, and the net zero transition, the demand for skills is changing. Our forecasts show that the greatest need of the UK labour market in the next 10 years will be in the human health and social care sector, as well as the highly skilled professional, scientific & services sector. Better targeting university output will raise the value of course content and strengthen the relationship between universities, opportunity, and the economy. This might be achieved through improving the provision of apprenticeships, which are lacking in the UK compared to other economies. Universities could also be integrated more effectively into local government and their growth plans, as well as with local business needs, to better align their educational output to local skills gaps and research needs.

Click on the button to read the full report:

Showcase your university’s economic and social impact

We have partnered with universities to measure their contribution to local economies and communities. If you’d like to understand how we can support your institution, fill in the form to connect with our team today.

Tags:

Related Reports

UK: Key themes 2026 – Sluggish growth and fiscal worries

We think 2026 will be another challenging year for the UK economy – our GDP growth forecast of 1% is at the bottom of the consensus. Four themes will be key to the outlook, in our view.

Find Out More

Nordics: Key themes 2026 – Bright spots emerging

We forecast growth across the Nordic economies to diverge somewhat next year but share the same underlying drivers.

Find Out More

Little by little—Manchester is closing the output gap

Greater Manchester has led the UK economy since 2008, driven by knowledge jobs, transport upgrades, and housing growth—but can prosperity reach its outer districts?

Find Out More

Powering the UK Data Boom: The Nuclear Solution to the UK’s Data Centre Energy Crunch

The UK’s data centre sector is expanding rapidly as digitalisation, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence (AI) drive surging demand for high-performance computing infrastructure.

Find Out More