How can demographic trends inform local investment needs and priorities?

Over the past decade, the UK population has continued to grow steadily, recording stronger growth rates than many European peer nations. This has largely been driven by the continued growth in international migration.

Yet, as observed elsewhere in Europe, the UK population is ageing. And with the latest ONS data showing the UK’s fertility rate has fallen to the lowest rate on record, further pressure is being placed on these already concerning demographic trends. This will have implications for the demand for health and social services, spending on pensions, and tax revenues, while a shrinking working-age cohort will pose challenges to the labour supply. But due to varying demographic trends at the local level, what this means for investment needs and priorities will be location specific.

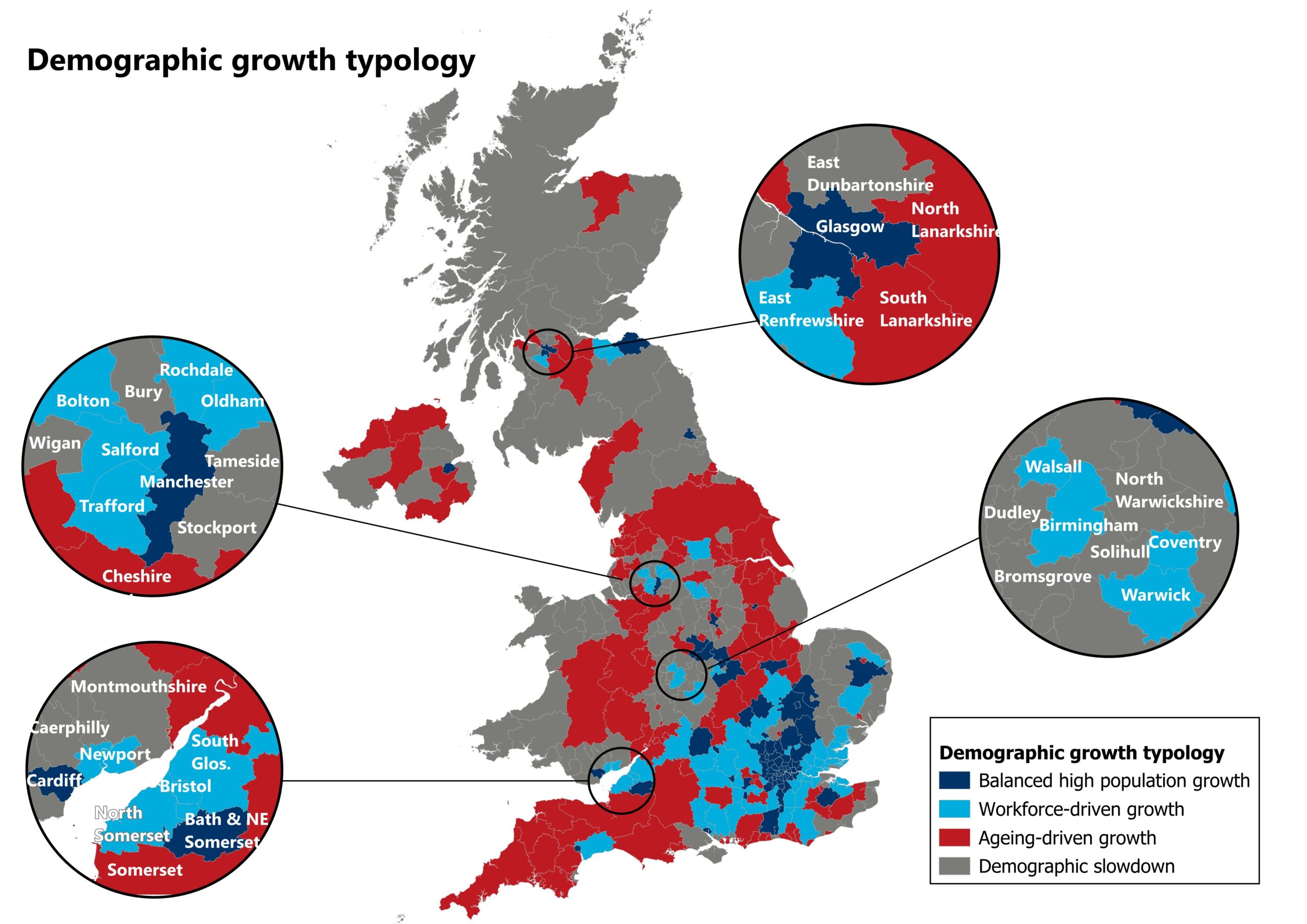

By analysing forecast growth rates for two key age groups—the working-age population (16–64) and those aged 65 and over—across all UK local authorities and comparing them to national trends, we have created a typology of investment need by place. Four typology groups, based on how their population is expected to change relative to the national average, have allowed us to develop a way of grouping investment needs by a place’s demographic factors (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Varying demographic trends across the UK

While local insight and contextual understanding remain essential for informed investment decisions, the four typology groups—workforce-driven growth, ageing-driven growth, balanced and high population growth, demographic slowdown—can help identify potential market opportunities and guide strategic investment planning.

For example, local authorities relying on workforce-driven growth are expected to see their working-age population grow at a higher rate than the UK average over the next decade, while their over-65 population is anticipated to grow slower than the average. These local authorities are mainly located in the Greater South East (but excluding London) and in major urban areas, including both core centres (Bristol, Birmingham) and their periphery (South Gloucestershire, Walsall). With an increasing supply of labour and a less pressing ageing population challenge, these areas are likely to see stronger demand for affordable housing, schools, and modern commercial space.

In contrast, population growth in many local authorities will be driven by an ageing population, with the over-65 segment growing rapidly and the working-age population growing below average. These tend to be largely rural areas located across the country, as well as de-industrialised urban areas such as Hull and Nottingham. These trends create market opportunities around infrastructure tailored to older residents, including assisted-living housing, healthcare facilities, and community centres. It is important to note that potentially strong demand for this type of infrastructure does not mean that there will not be localised need for family housing, schools, or commercial space, as younger residents and families will continue to live and work in these communities.

In between the two aforementioned categories sit the local authorities expected to experience both balanced and high population growth, with above-average growth in both working-age and over-65 populations. This includes most of the London boroughs, several mainly residential areas (Horsham, Bracknell Forest), and growing regional economies (Cambridge, Reading). Outside of the South East, Manchester, Glasgow, and Belfast also fall in that category. Here, investment opportunities go across the board and are less easy to prioritise without detailed, hyperlocal analysis.

Finally, a large share of UK local authorities are expected to face below-average growth in both their working-age and over-65 populations, resulting in a demographic slowdown, if not a decline. For rural areas falling into this category, market opportunities might be concentrated on more niche markets, such as tourism infrastructure. Some urban local authorities with relatively weak economic growth prospects also fall into this category. Such urban areas with larger market sizes, including Liverpool and Doncaster, could remain attractive for housing and commercial development projects, despite a weaking demographic profile.

The Oxford Economics Global Cities Index ranks the largest 1,000 cities in the world based on five categories: Economics, Human Capital, Quality of Life, Environment and Governance. Underpinned by Oxford Economics’ Global Cities Service, the index provides a consistent framework for assessing the strengths and weaknesses of urban economies across a total of 27 indicators. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most detailed cities index in the industry. To download the full report, please fill out the form below.

Related Reports

Cities at the frontier of sustainability: insights from the Global Cities Index 2025 | Greenomics podcast

Explore insights from the Global Cities Index on city sustainability, key results and how governments can drive sustainable urban development.

Find Out More

Tariffs and tensions are reshaping city economies

Tariff policies, rising geopolitical tensions and unprecedented uncertainty are putting pressure on cities and regions across the world.

Find Out More

The world’s leading Sustainable Cities: Built for long-term prosperity

Oxford Economics defined the archetypes using a range of metrics from all five categories of the Global Cities Index, with each archetype focusing on a different set of common traits.

Find Out More

Top regional hubs to watch in 2025

Oxford Economics defined the archetypes using a range of metrics from all five categories of the Global Cities Index, with each archetype focusing on a different set of common traits.

Find Out More