Blog | 02 Aug 2022

For global economic recovery, policy must focus on three key gender-forward reforms

Elizabeth Martindale

Economist

It is no secret that Covid-19 has disproportionately impacted women’s lives and their economic opportunities. As governments focus on stimulating economic recovery, they must now prioritise measures that help women. Indeed, McKinsey & Co has estimated that adopting gender-specific policies now could add $13 trillion to global GDP by 2030 compared to a loss of $1 trillion if countries choose gender-regressive recovery plans.

There are three key areas where policy action will help women who have been more affected by Covid-19 than men:

1. The labour market

A previous blog by Oxford Economics showed that women were more likely to work part-time, and were thus more vulnerable as these positions were more at risk. According to separate research from the United Nations, 40% of the global female workforce work in harder-hit sectors. Ensuring that more women are working won’t just boost employment and spending but will also benefit employers—Oxford Economics and IBM found that organisations that prioritise gender equality within their workforce are 12% more likely to outperform their competitors in terms of profit growth.

2. Time/unpaid work

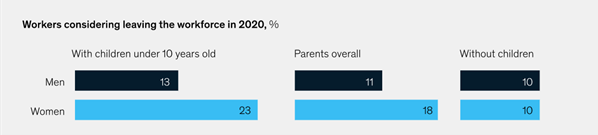

The time women can spend in the labour market is unfairly restricted due to childcare and other household responsibilities. This unpaid work has always been disproportionately more of a woman’s “duty”—according to the International Labour Organization, women undertook 76.2% of total (global) unpaid work in 2018. Surprisingly, even though men are also spending more time at home, lockdowns globally have actually led to a widening of the inequality in time spent on unpaid work. The figure below shows that women with young children were almost twice as likely to consider leaving the workforce than men with young children during Covid-19. In essence, the more time women spend on unpaid work, the less time they have to contribute to the economy.

The proportion of women and men considering leaving the labour market in 2020 by parental status

Source: McKinsey & Co, 2021

3. Mobility

As well as having less time, women were also less mobile than men during the pandemic. In general, women are more reliant on public transport than men, who are more likely to drive. Lockdowns and social distancing have led to capacity of some services decreasing by 80%-90%–there have been cases where women have been left stranded on isolated roads after buses capped the number of passengers they would take. Unjustly, resource-poor women struggled to get to work—and so became even more economically disadvantaged—due to a lack of transport alternatives during Covid-19.

According to the United Nations, just one-tenth of policies aimed at boosting the post-Covid economy are specifically designed to provide economic support for women. To improve this, governments should intervene in areas such as work-from-home arrangements, childcare, and city planning. Allowing women to have greater flexibility around their working time means that they can work and tend to their children. It also gives men more time to reduce women’s unpaid work burden and increase gender equality. To ensure a more gender-equal division of care responsibilities and time spent in the labour market, governments should provide more affordable state childcare and financial incentives for both parents to take parental leave and return to work. Finally, policies that allow women to be more mobile or reduce their journey time to and from work are important, such as setting up more local facilities/amenities, matching workers to local jobs, and providing subsidised public transport with more frequent services.

Author

Elizabeth Martindale

Economist

+44 (0) 203 910 8154

Elizabeth Martindale

Economist

London, United Kingdom

Since joining Oxford Economics in February 2022, Elizabeth has worked on various economic and social impact projects. Prior to this, Elizabeth worked as a Lecturer for the Economics Department at Manchester Metropolitan University. Elizabeth also has experience as a Financial Consultant at KPMG Luxembourg, which allowed her to gain French and German language skills. Elizabeth holds an MSc in Development Economics and Policy from The University of Manchester and a BSc (Hons) in Economics from Manchester Metropolitan University. Her main research specialisations include Gender, Health Economics, Inequality, and Governance.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Don’t write the Eurozone consumer off just yet

Eurozone growth in 2025 will rely on consumers. There were positive signs in H2 last year, with consumers starting to deploy their real income gains and the impact of lower rates feeding through. However, we don't think solid H2 outturns signal a sustained increase in momentum. Instead, we expect spending growth to stabilise around the current pace, totalling 1.5% in 2025.

Find Out More

Post

Parsing US federal job cuts by metro

Cuts to the Federal government workforce, which we estimate to be 200,000 in 2025, will have a modest impact nationally, but more significant implications for the Washington, DC metropolitan economy as it accounts for 17% of all non-military federal jobs in the US.

Find Out More

Post

Taking stock of this week’s twists and turns in US tariff policy

A North American trade war unfolded in dramatic fashion this week.

Find Out More