Blog | 09 Dec 2021

Home working and remote rural places: Evidence, problems, and a proposal

Richard Holt

Director of Global Cities Research

Over the last year and a half, many office workers have decided they can work from almost anywhere with a desk, a decent internet connection, and enough space. People say they are just as productive at home as when they are in the office. If so, then maybe rural towns and villages can now compete with the big city, when it comes to productive desk-based working. Perhaps cities will no longer be the great drivers of growth?

There may be lessons to be learned from recent history. A decade ago, the hot topic was broadband and whether it could help remote and previously under-performing local areas raise their competitiveness—reversing a centuries-old pattern in which the most remote places tend to have the lowest incomes per head.

It was hoped that for employers and workers in such locations, broadband would help to overcome the problems of remoteness. Better digital connectivity would lower costs, and it would enable innovation, for example by making it easier to collaborate. Plus, broadband would allow for more flexible patterns of work, including working at home, in areas where travel to work can be very problematic. And broadband would lower the barriers to starting a business, boosting rural entrepreneurship. Much of this sounds very similar to the debates we are having today; the motivations are different, but the arguments are very similar.

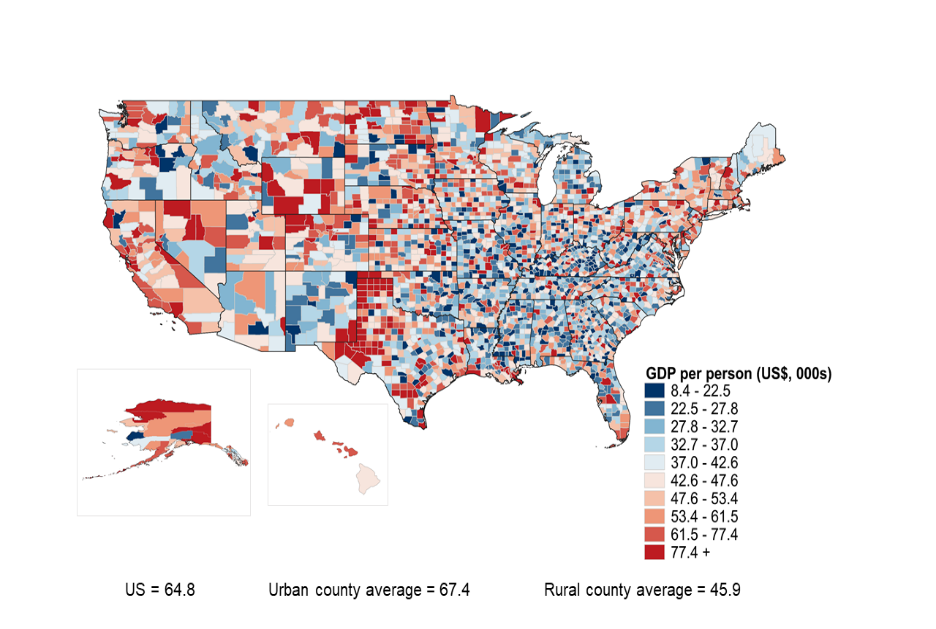

Rural areas have lower income per head than urban areas: evidence from the US, 2019

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Census Bureau, Oxford Economics

What were the outcomes? The What Works Centre at the London School of Economics has examined more than 1,000 research papers on the subject, whittled them down to just 16 that follow robust methodologies—half from the US and half from Europe—and has drawn some conclusions. It finds that when broadband was introduced into a local area it sometimes raised companies’ productivity, but not always and not necessarily by much, with a lot depending on whether complementary investments were made, and on the skill levels of those involved.

A study in the US, reviewed by the LSE team, showed that spreading broadband to rural counties encouraged the formation of new local businesses—but only for the least remote areas. Proximity to a city was still a vital driver of company formation, even though the new technology was supposed to facilitate remote working. Similarly, a UK study found that broadband actually did more to stimulate urban economies than rural ones, when all other factors were allowed for—suggesting that digital contacts do not fully replace real ones.

More positively, one study found that expanding broadband into a location had a positive impact on women’s participation in the labour market. And crucially, there was evidence from some studies that providing broadband to a local area might encourage suitably skilled people to move to it—which may be closely analogous to the post-pandemic case of people leaving their city offices to work in a semi-urban, rural, or remote seaside location.

Of course, the adoption of broadband a decade ago is not identical to the possible spread of remote working today. But that does not mean it tells us nothing. First, distance does not die, as a recent Oxford Economics Research Briefing confirms. Second, while new technology may open up opportunities, it particularly increases the options available to those who, thanks to their professional or technical skills, are already in the strongest position in the labour market.

There is a lesson for policy makers, too: don’t assume that “working from home” will solve all the problems of remote rural communities. Government agencies should continue to encourage and support online business communities, linking together those in cities with those in rural communities, using the new digital technologies to provide forums for exchanging ideas and opportunities, training, and help with technical matters such as product standards. The aim would be to build business networks that jump geographical boundaries. Government’s role would be catalytic: getting the networks in place, then watching them grow. The cost would be low, the potential large.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

US Bifurcated ꟷ Economic backdrop deepens racial disparities

Black and Hispanic households have experienced more inflation than other groups since the reopening of the economy from the pandemic lockdowns. Although there've been many phases of high inflation, some have disproportionately hurt these minority groups, such as the jump in energy prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, with the ensuing surge in rental inflation further setting them back.

Find Out More

Post

The rise of Southern India’s business service hubs

Over the next five years, India is set to be one of the fastest-growing major economies across Asia Pacific, lead by the performance of its IT and business services. The Southern states of Karnataka and Telangana are at the forefront of this success as they are home to two of India’s most rapidly growing cities and productive cities—Bengaluru and Hyderabad.

Find Out More

Post

Tech-enabled productivity may mean a job-lite expansion in Asia Pacific

The US is undergoing or heading towards a 'jobless expansion'. Asian economies, likewise, will probably experience slow job growth over the next few years, accompanied by mechanically rising productivity gains. In the near term, the drag on the job market is likely to come from cyclically weak demand for labour. But further down the line, it is the shrinking labour supply that will weigh more heavily on employment growth.

Find Out More