Blog | 15 Aug 2022

Food, inflation, and regime stability in Africa

Pieter Scribante

Political Economist, Oxford Economics Africa

Supply chain and trade disruptions resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic exposed the inherent fragilities associated with relying on imports to meet domestic food needs. Food insecurity can very quickly become a concern in net-food-importing countries. With the war in Ukraine disrupting international trade and pressuring global food supplies, the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) have sounded the alarm of increasing risks of hunger, famine, and starvation, with developing countries the most vulnerable.

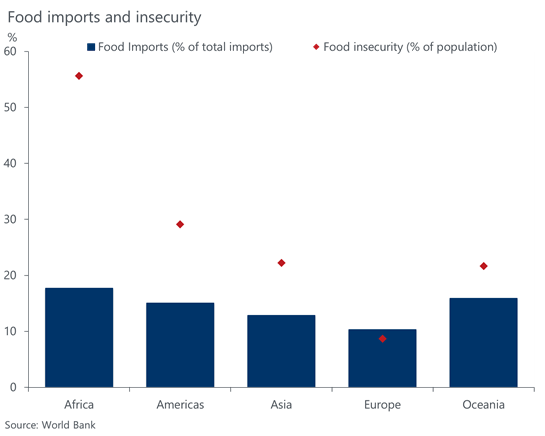

In Africa, food imports accounted for an average of 18% of the continent’s import profile in 2019. While this is in line with the rest of the globe, and only slightly above that of Oceania (16% of total imports), food insecurity is far more prevalent in Africa. According to the World Bank, an average of 55.6% of households in Africa experienced some level of food insecurity in 2019, far above the second-most vulnerable region, the Americas (29.1% of households). This is especially worrying given Africa’s fast-growing population and high vulnerability to climate change, both which threaten food security further.

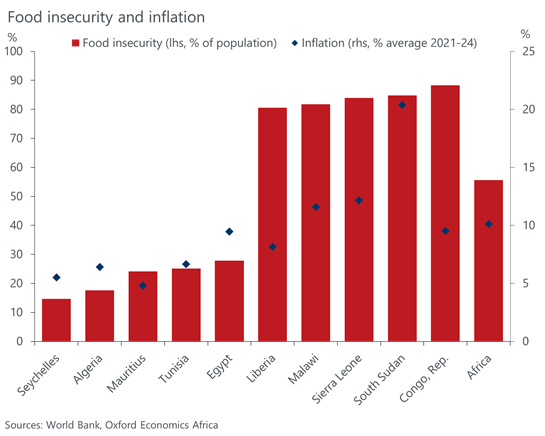

There are important macroeconomic considerations associated with food insecurity in Africa. First fiscal deficits in food-insecure countries tend to be wider and expenditures more volatile as spending is often directed towards emergency food aid or subsidies at the expense of long-term development spending. Second, the volatile nature of food prices mean that inflation tends to be higher in food-insecure and net-food-importing countries. Finally, economic growth and development tend to lag in food-insecure countries. While the causality does run both ways (weak economic growth increases food insecurity, and vice-versa), countries with inadequate food supplies and higher food insecurity are more prone to fall into low-growth traps.

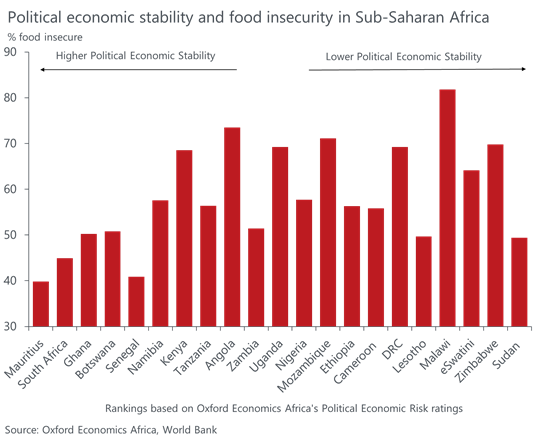

The political economy of regime stability and food security is vital in Africa. The two are highly linked, as countries with secure food supplies are less prone to violence and unrest, and have lower levels of political economic risks. Before Sudan’s former President, Omar Al-Bashir, was ousted in 2019, the country experienced droughts and an agricultural downturn that reduced food supplies and led to growing food insecurity, rising inflation and protests. Mr. Al-Bashir survived the Arab Springs, civil war, several coups attempts and the loss of 75% of Sudan’s oil reserves when South Sudan seceded in 2011, but his 30-year reign came to an end following months of demonstrations by dissatisfied and hungry protestors.

The political fallout of rising prices and food insecurity have started to show in the form of protests in countries that are normally very stable, like Mauritius and Morocco, while other countries such as Egypt have postponed plans to scrap food subsidies. Countries with higher political economic fragility, like Eswatini, Zimbabwe and Sudan, are more exposed to the inherent vulnerabilities of food insecurity and are at high risk of unrest and protests if food supplies decline and prices rise. However, the political salience of food security means that even more stable countries, particularly Ghana, Kenya and Tunisia, run the risk of unrest if food security deteriorates in coming months.

Author

Pieter Scribante

Political Economist, Oxford Economics Africa

Pieter Scribante

Political Economist, Oxford Economics Africa

Paarl, South Africa

Pieter is a political economist at Oxford Economics Africa, first joining the firm in 2019. He holds an MSc in Political Science and Political Economy from the London School of Economics (LSE) and is the principal analyst for Nigeria and Mauritius. Pieter specialises in macroeconomics and political-economic risk analysis.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

The Green Leap: More promises but little innovation at COP30

The COP30 in November made some ambitious commitments to scaling up climate finance. Until those materialise, initiatives to leverage natural endowments for financing may be more attractive to African countries, especially those with high forest cover.

Find Out More

Post

The Green Leap: Unlocking climate financing at COP30 for Africa

The scaling of climate finance for developing countries will take centre stage at the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) starting today, in Brazil. Leaders will grapple with how to plug the gaping shortfall in funds needed to help developing economies curb emissions and adapt to climate shocks. Reforming the global financial architecture will be a key discussion.

Find Out More

Post

Continental oil kings missing out on evolving oil dynamics

Uncertainty around global growth has widened the range of possible outcomes for oil consumption. While demand growth currently lags behind supply, stronger-than-expected trade or industrial activity could lift demand above projections. This brief explores whether Nigeria and Algeria are positioned to take advantage of such an upside.

Find Out More