Blog | 19 Aug 2021

Don’t fear the robots—but do prepare for them

Automation and robotization are rapidly transforming industries across the world: The global stock of robots has more than doubled since 2010. This surge has been driven by lower cost, better accessibility, and higher productivity of robots, and further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout. During the pandemic, small and large companies alike significantly expanded their use of robots to continue operating under tight labor conditions—reports suggest that orders for robots increased by 20% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2021 alone.

Historically, automation has improved productivity, per capita output, and living standards. Despite concerns of policymakers that the pandemic-induced automation drive might displace more labor than it creates, we believe that overall, the past trend will persist, and workers will continue to benefit from the productivity boost. While robotization does tend to displace some workers and cause short-term disruptions in the labor market, it simultaneously increases demand for skilled labor, ultimately creating more jobs than it destroys. Technological advancement will change the way we work, and the skills needed in the modern labor force, but we don’t see this leading to a decline in the demand for workers in aggregate in our baseline forecast.

That said, there are other possible (though less likely) outcomes to this increase in robotization. Some recent studies have fueled the growing anxiety over automation implications, suggesting that employment may not benefit from upcoming technological advancements the way it has done in the past and instead will fall victim to substantial displacement effects. These critics argue that, due to the exponential improvements in AI and machine learning, computers are increasingly able to perform cognitive tasks—and thus gain the ability to replace high-skilled workers. One study suggests that 47% of US jobs fall into the high-risk category of being replaced by machines by 2030.

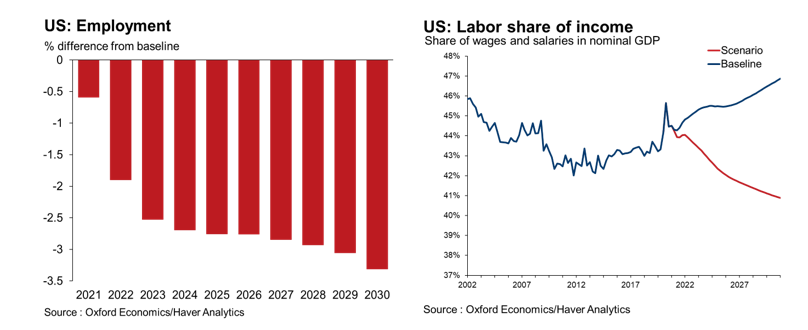

Oxford Economics modeled a scenario that explores this potential future displacement of labor by robots. Drawing on our recent research into robotization trends in the manufacturing sector, we asked what would happen if the increase in robot density in manufacturing were to be replicated in other sectors, including services. Crucially, this would require robots to perform advanced cognitive tasks usually associated with the service industry (e.g., retail, customer service, healthcare etc.). We applied this assumption regarding the quantitative impacts of increased robot density on employment, wages, and total factor productivity, and ran this through our Global Economic Model.

The outcome of this alternative scenario is a world where more goods and services are produced because of increased productivity, but the returns of higher productivity increasingly accrue to capital instead of labor. Conversely, real wages in the economy decline as labor becomes more substitutable, leading to a declining labor share in income.

Though this scenario is an interesting thought experiment, it is unlikely because it goes against the historical precedent of technology creating more jobs than it destroys. Our baseline projections assume automation will create positive impacts on employment and productivity. Nevertheless, the alternate scenario of a decrease in the labor share of income cannot be discounted entirely given the accelerating pace of technological progress.

To mitigate risks arising from automation and robotization, workers need to increasingly keep pace with the rapid advancement in technology through education and re-skilling to become complementary to new technology rather than be replaced by it. Policymakers can facilitate this effort through mapping out the existing skillsets at the local level through labor surveys and analyze this data alongside regional business trends. Moreover, companies need to be incentivized to engage in local programs to retrain workers with relevant skills. Broader macroeconomic policy options can include infrastructural investment, human capital development through STEM education or training initiatives, and welfare programs like universal basic income.

The design and implementation of labor and social policies in the near future will define the impact of robotization on countries and its people. Robotization is inevitable. Active government intervention can steer the economy towards more efficiency and equality. However, a laissez-faire approach can lead to a society with skill barriers to labor mobility.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

MENA – Latest Trends

Our blog will allow you to keep abreast of all the latest regional developments and trends as we share with you a selection of our latest economic analysis and forecasts. To provide you with the most insightful and incisive reports we combine our global expertise in forecasting and analysis with the local knowledge of our team of economists.

Find Out More

Post

You don’t have to be an IT expert to lead on AI

The adoption curve for AI will vary across companies but, according to our data, it’s probably already in use in customer service and marketing—areas where women are more likely to hold leadership roles.

Find Out More

Post

The latest export from China is … deflation

We expect Chinese export price deflation to provide a helpful tailwind in the struggle to bring EM inflation back to target.

Find Out More