Ungated Post | 11 Jun 2018

Bad news from the black stuff as oil surges – but keep calm

Modern economic history since the 1970s is littered with episodes of oil shocks, with surging crude prices triggering global recessions. With the cost of benchmark Brent crude having surged by 62% over the past year or so, to levels around $77 a barrel, anxieties are mounting over the implications. So just how serious is the bad news from the black stuff?

Oxford Economics recently raised our baseline forecast for oil to $85 a barrel in the second half of this year. And oil price spikes remain one of the fastest and most potent redistributors of income, wealth and capital that the global economy can throw up.

Yet, in spite of this, we remain relatively sanguine over the fallout from this episode of sharply higher oil prices, and we see a series of reasons to be less pessimistic this time around.

Keep calm and carry on

First, the recent price jump looks modest by historical standards.

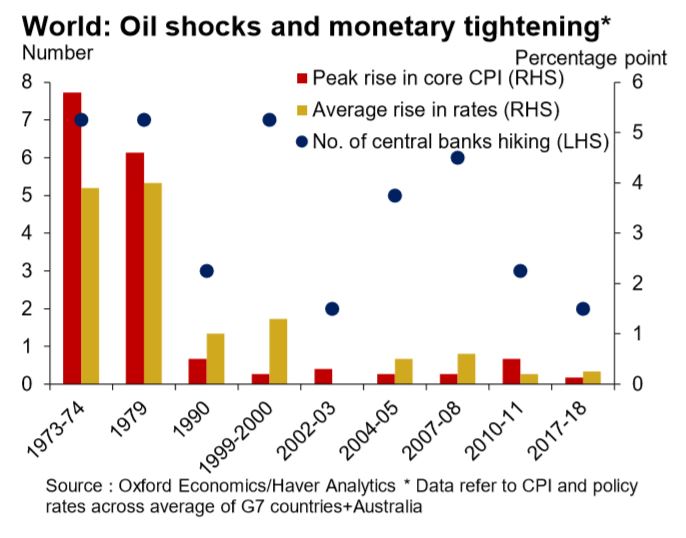

Although the cost of Brent crude is up by some 60%, the magnitude of many other noted oil shocks has been much larger – a 278% increase in the 1973-74 episode, 190% in 1979, and a 110% spike in the case of 2007-08, coinciding with the global financial crisis. The current situation, at least so far, is more similar to the cases in 2002-03 (49%) and 2010-11 (53%) and it comes at a time of robust and rising world economic growth.

Crucially, a key reason for relative calm is the waning effect on both growth and inflation that oil shocks have had over decades. A key factor is that the importance of oil in the global economy (the so-called oil intensity of demand) has declined considerably. We estimate that oil demand per unit of world economic output (GDP) had dropped by 60% since 1973.

And while central banks in the high-inflation Seventies were forced to respond aggressively to soaring oil price to head-off knock-on effect to price pressures through second-round effects, as business responded with higher prices and consumers with demands for more pay, today there is greater room for manoeuvre.

Not so much to round two

Greater confidence that credible central banks will keep inflation under control has anchored expectations of future inflation so that second-round effects from pay demands and price rises are more limited, allowing a more measured and muted response from interest-rate setters.

We see the higher oil prices we forecast as spelling only a short-lived pick-up in energy inflation, adding up to 1 percentage point to overall consumer price inflation in the advanced economies.

With high employment meaning jobs markets are tight, there are risks of a bigger-than-normal response from wage demands that would add to the inflationary effects. But oil price surges in 1999-2000 and 2007-08 also came amid tight jobs market conditions but did not see excessive wage growth.

Our conclusion is that while central banks will watch-out for inflation risks, they will be restrained in their response and be wary of responding with higher interest rates that could snuff out growth. In the 2007-08 case, the average response was a 0.6 point rise in rates – a fraction of what was seen in earlier episodes.

A triple whammy for vulnerable EMs

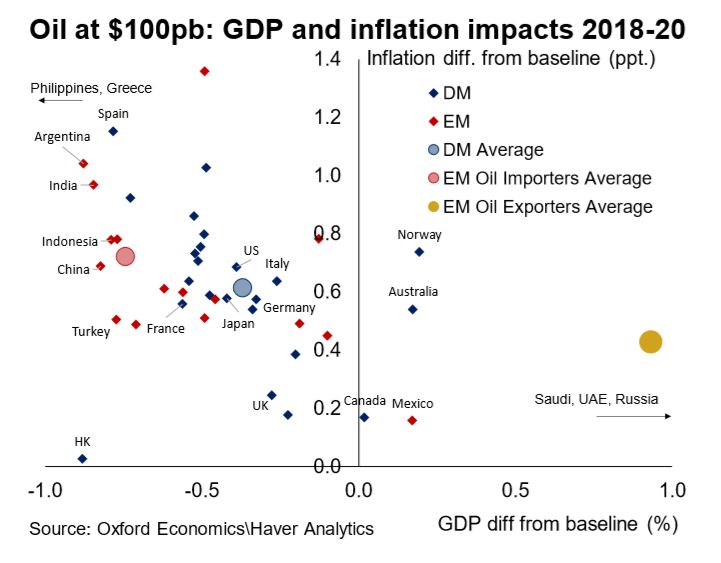

Dangers would mount, however, if oil prices climb still higher. We ran a simulation on the Oxford Economics Global Economic Model of the effects oil reaching $100 a barrel by the autumn.

Again, we found this would not trigger a major economic slowdown or inflation surge, although it would cut the level of global GDP by 0.7% in 2020 versus where it would otherwise have reached, with inflation rising 1.2 percentage points above our baseline forecast. But oil prices at this level would sour the ‘Goldilocks’ environment in the world economy.

The biggest risks from the surge in the cost of crude are for emerging markets, and especially those that are heavily reliant on oil imports. These economies are exposed to hits from a reversal in the terms of trade (the relative costs of exports and imports), the strength of the dollar, reversals in capital flows, and recent cuts in fuel subsidies that expose their consumers to higher prices. Most affected are the already-vulnerable economies of Greece, Argentina and Turkey. China and India are also exposed to a sharp deterioration of the trade-off between output and inflation.

But we also believe that emerging markets are bolstered by stronger frameworks of economic policy than in other recent decades. The greatest worries are over those economies where the toll from higher oil prices is a threat to political stability as seen in episodes of emerging unrest with striking truckers in Brazil, demands in India for price controls on the state oil and gas company, and plans by governments in Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam for more fuel subsidies to insulate consumers.

Read more about the impact of higher oil price here

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Oxford Economics Expands Regional Presence with the Launch of Japanese Website

Oxford Economics, the world’s leading independent economic advisory firm, is excited to announce the launch of its new Japanese website. This important milestone reflects our ongoing commitment to broadening our presence in key regional markets and strengthening our ability to provide localised, high-quality economic insights to businesses and decision-makers in Japan.

Find Out More

Post

Oxford Economics Invests £2 Million in The Data City to Drive AI-Powered Business Intelligence

Oxford Economics is pleased to announce a £2 million investment in The Data City, a UK based cutting-edge real-time company classification platform.

Find Out More

Post

Oxford Economics Launches Megatrends Scenarios Service

Oxford Economics releases its first Megatrends Scenarios service, providing critical insights into the future of the global economy.

Find Out More