Blog | 28 Jun 2021

Regime change: should we get used to high inflation?

Innes McFee

Managing Director of Macro and Investor Services

Inflation has become the all-consuming focus of investors’ attention in recent weeks. On the surface the story is simple—transitory factors (including the supply bottlenecks created by the reopening and a recent surge in commodity prices) have pushed inflation well above target in many economies but, as they fade, inflation is set to return to target. Consequently, markets have been pretty sanguine about the prospects of higher inflation.

Our recent research, however, has been aimed at asking a deeper question: What if the changes in the economy are enough to push us out of our current low-inflation regime into a high-inflation regime similar to the US and UK in the late 1970s and ’80s, or Iceland after the global financial crisis?

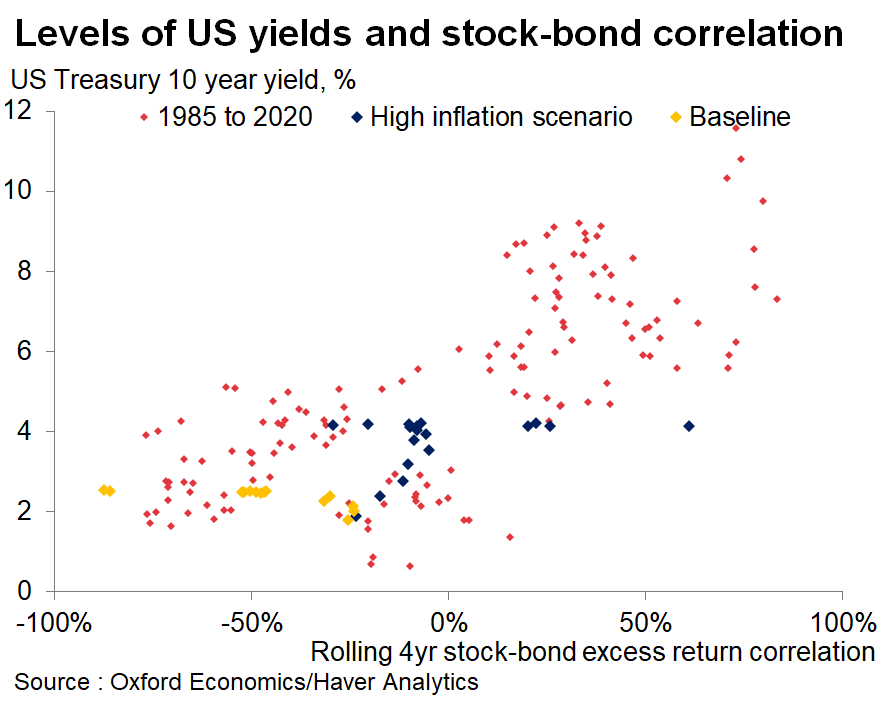

Observing regime change in real time is very difficult. But moving to a high-inflation regime, defined as inflation consistently above 5%, is of huge significance. Not only might it mean that some dormant economic relationships would be resurrected—like the trade-off between unemployment and inflation—but also that financial markets would react differently. The very cornerstone of modern portfolio construction is a negative relationship between stock market and bond market excess returns. This diversification between bonds and stocks protects investors from wild swings in their returns. In a high-inflation environment, this correlation flips from negative to positive, as we demonstrate using our Global Economic Model to simulate a scenario of higher inflation expectations, leaving investors dangerously exposed to the economic cycle.

It is not just financial investors who should be concerned. Real estate capitalisation rates tend to be positively correlated with interest rates, but this is because in the current regime underlying demand has tended to drive both up at the same time. In a high-inflation regime, it is likely that higher interest rates and inflation would likely coincide with lower real estate returns. All of a sudden, the conventional wisdom that real estate is an inflation hedge may no longer ring true.

So what changes in a post-Covid world might push us to a high-inflation regime? There are three potential candidates:

1. More active fiscal policy. The pandemic appears to have sealed the end of the consensus on fiscal austerity, which has helped to dramatically raise the outlook for demand, particularly in the US.

1. More active fiscal policy. The pandemic appears to have sealed the end of the consensus on fiscal austerity, which has helped to dramatically raise the outlook for demand, particularly in the US.

2. Blurred central bank mandates. The Fed’s move to average inflation targeting as well as possible future changes to the ECB’s mandate, if repeated, could destabilise the inflation expectations of households and businesses.

3. Knock-on impacts of the current inflation spike. Over the next few months global inflation is set to be the highest in almost a decade, squeezing real incomes and profit margins. In a fast-growing economy, combined with a blurred central bank mandate, these shocks could translate into wage- and price-setting behaviour.

Nevertheless, our econometric modelling of inflation regimes over the past 60 years and across 20 economies shows that once in a low-inflation regime there is only around a 10% probability of switching to a high-inflation regime. Consistent with that finding, our historical analysis also shows that regime changes do not happen overnight, and occur because of a combination of shocks. These shocks have included aggressive expansionary monetary and fiscal policy, errors in policy that damage credibility, and ‘de-anchoring’ episodes.

In the current context this seems a fair assessment. If anything, the pandemic has exacerbated some of the secular forces that have been pushing inflation down for the last decade. An aging population, increasing levels of automation and a highly globalized economy are all still powerful disinflationary forces that we expect to continue over the next decade.

On that basis we expect the inflation environment to remain relatively benign, with inflation probably overshooting targets more than in the past decade, albeit not by much. While the evidence suggesting a shift to a high-inflation regime can’t be ruled out, for now we would only give it a probability of around 10% for the global economy, and 15% for the US. That’s still enough to justify investor angst given the profound consequences.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

MENA – Latest Trends

Our blog will allow you to keep abreast of all the latest regional developments and trends as we share with you a selection of our latest economic analysis and forecasts. To provide you with the most insightful and incisive reports we combine our global expertise in forecasting and analysis with the local knowledge of our team of economists.

Find Out More

Post

You don’t have to be an IT expert to lead on AI

The adoption curve for AI will vary across companies but, according to our data, it’s probably already in use in customer service and marketing—areas where women are more likely to hold leadership roles.

Find Out More

Post

The latest export from China is … deflation

We expect Chinese export price deflation to provide a helpful tailwind in the struggle to bring EM inflation back to target.

Find Out More