Blog | 14 Jun 2022

Partnerships are an imperative in the Covid-normal, zero-emissions bus transition

Nothing’s guaranteed but death and taxes, as the adage goes. But we can be reasonably sure when 2030s public policymakers look back at the preceding decade, they’ll see the outsourced global bus industry as having undergone a paradigm shift. This will be down to two things: the Covid epidemic; and the mass decarbonisation of the bus fleet into Zero-Emission Buses (ZEBs).

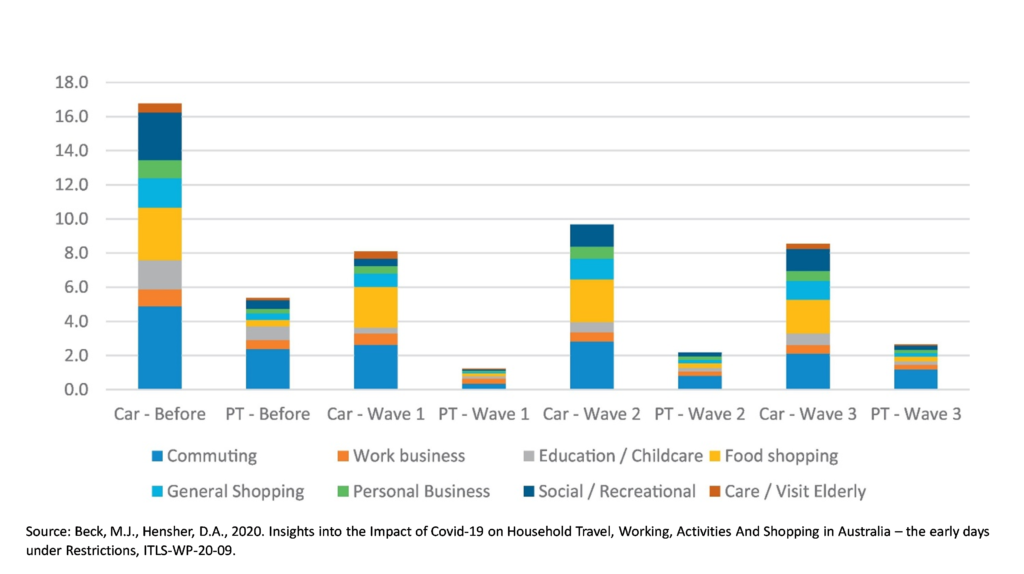

The figure below shows the impacts of the Covid lockdown on bus ridership in Australian cities, a pattern repeated in most urban areas within the developed world. In the varying stages of restrictions, public transport use plummeted when categories of workers were mandated to work from home and schools were closed. Patronage crept up with each progressive lockdown, but still hasn’t recovered to its former levels—and many experts predict it won’t.

For governments operating their own services and fleets, this meant absorbing cost and revenue losses. In cities where services are franchised, such as Sydney, London, Singapore, Amsterdam, and Dublin, private operators needed to be insulated to some degree by the state procurer. This entailed a combination of payments for minimum or full-service levels, and the removal of patronage and performance incentives, to keep them “whole.”

This government-backed safety net is the reason why investors presently see bus franchising as a relative haven in these volatile economic times. The sector offers government-backed payments, long-term contracts, zero or little demand risk, and little potential for asset stranding. Investors keep investing in this space provided the outlook for an operator they are acquiring is to hold, or gain, “turf.” This is known as recontracting risk and is fundamental to gearing finance for a bus company acquisition.

Conversely, the ZEB (Zero Emission Bus) global revolution is being driven by government carbon neutrality policies. Significant commitments have been made to replace diesel buses with electric-powered ones, often in relatively short periods of time. Some nations have mandated no new diesel buses can be purchased beyond a certain date. In other places operators are pushing ahead themselves to gain scale; for example in Canada, Transdev are investing €3 million in electric school buses.

But ZEBs are very capital intensive. To accommodate electric fleet, bus depots must become akin to power stations, and local electricity grids need significant upgrading. ZEBs make bus franchises more like the marriage of an infrastructure PPP and a service contract—the capital intensity and cost structure of the sector shifts dramatically, and so does the risk profile. Buying a ZEB is not the same as buying a lawnmower.

The delivery of ZEBs will require huge capital investment, and it must come from the state or be backed by the state to attract private capital. For infrastructure investors, ZEBs present a wholly different risk profile. This raises the vital nature of recontracting exposure even more, as not only would contracts be lost, but significant assets potentially stranded, and this risk will deter investment.

Such a risk profile butts up directly against the concept of competitive public tendering, for many seen as the gateway to best public value. Tendering only works well when the product is clear and the timeline uncomplicated. This is not the case for the ZEB transition with its evolving technology at times of inflationary risk.

The old approach of awarding contracts to a service operator would appear to be coming to an end. Future bidding groups will be operators, electricity providers, charging equipment suppliers, and battery makers. No investor will put money into something of that scale if the business they are acquiring looks set to lose their contracts in a short period of time.

Long-term partnership agreements will be essential to attract private capital into the global bus market as the world emerges from Covid restrictions. Recontracting risk remains the key variable. It is impossible to tender whilst there are large mammals in the corner of the room. Partnerships, not prescriptive contracts, will be imperative.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Labour’s very cautious approach to regional economics

We do not expect that a future Labour government would have much more impact on regional imbalances in the UK than present or past governments, although their Green Growth Plan might help, as might their emphasis on improving supply chains, especially if linked to encouraging more innovation. Progress may therefore occur, but not quickly.

Find Out More

Post

Innovation Index: Are You Prepared to Shift from Disruption to Growth?

Oxford Economics and NTT Data fielded a survey of 1,000 North American business and IT executives in 2022 to uncover future strategies to mitigate disruption.

Find Out More

Post

Digital Platform Technologies and Innovation in Europe

This report, commissioned by Meta Platforms, Inc., assesses the role of digital platforms in enabling innovation in society, using Meta as a case study. It focuses on the role played by Meta’s digital infrastructure to drive the innovation of software developers and businesses in Europe.

Find Out More

Post

Policymakers must be honest about the winners and losers of clean energy transition and building a green economy

Achieving a net zero and carbon neutral world by 2050 is the defining challenge of our age. It relies on many partners working together to shoulder great costs, and to do so as equitably and efficiently as possible. It is important for policymakers to be honest about the challenges businesses, investors, and consumers will have to face if we are to halt global warming on the sort of timescales scientists are telling us is necessary.

Find Out More