Blog | 11 Oct 2022

Policy-makers must remember the energy crisis pain will not fall equally across society

Phil Thornton

Economics Editor

As spiralling energy prices threaten to cause huge pain for consumers and businesses, governments across Europe are rolling out initiatives to cap the impact. Despite that, poorer households are likely to be hardest hit and will need to take their own steps to strengthen their financial resilience.

The cost-of-living crisis gripping the UK and other European economies threatens to undermine households’ financial resilience. As well as mounting energy bills, soaring inflation and the prospect of further hikes in central bank interest rates will intensify pressure on consumers’ finances this winter.

In partnership with investment management firm Hargreaves Lansdown, Oxford Economics has designed the Savings and Resilience Barometer for Great Britain. The Barometer tracks five pillars of financial management—debt control, savings, insurance, pensions, and investment—and can be used to paint a holistic picture of trends in financial resilience both over time and between households.

While households may feel they are still emerging from the after-effects of the coronavirus pandemic, our analysis shows that in fact Covid-19 was associated with an improvement in households’ financial resilience, despite a record decline in economic output of 11.5% in 2020. This reflected an unprecedented level of government support and an enforced period of consumer restraint due to social distancing measures, meaning that UK consumers took the opportunity to collectively pay down their debts and build up their savings. Indeed, our headline barometer rose from 57.9 in 2019 to 61.3 at the end of 2021 on a scale of zero to 100.

Despite the positive aggregate trend, our analysis indicated that the improvement was spread rather unevenly across society, with those on lower incomes and with children at home less able to improve their resilience. As a result, significant vulnerabilities remain, even prior to the escalation in energy bills, with more than 15% of low-income households behind on a (non-mortgage) debt repayment or a household bill. And a third of the UK does not have access to savings that would cover at least three months of essential expenses.

In our June update, the impact of rampant inflation was becoming apparent. Based on our baseline forecast at the time, we projected that the average barometer score would fall back to 58.3 by the middle of next year, wiping out almost all of that pandemic-era gain.

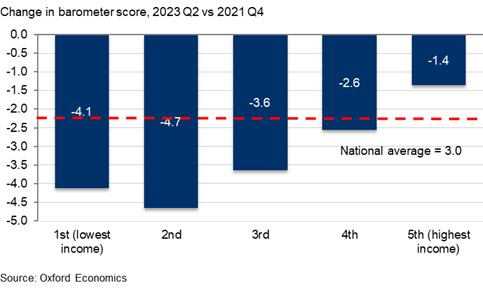

Moreover as Fig. 1 shows, the largest falls in financial resilience will be felt by the poorest segments of society. The poorest fifth of households will see a 4.1-point fall in their resilience while the second poorest fifth will see a drop of almost five points. The richest group of households will only see a 1.4-point drop. The key reason for this is that in lower-income households day-to-day essentials—notably energy—account typically account for a higher share of spending. For example, in the UK that will average 41% of spending among the poorest 20% of households next year, a share that drops to 12.4% for the richest 20%.

Fig 1. Weakening in financial resilience unevenly felt across society

Although the insights from the barometer are specific to the UK, we would expect the general trend—a disproportionate shock to the finances of lower income households that are typically less well positioned to cope—to be mirrored across other economies in Europe. Moreover, the sheer scale of the shock seems set to trigger a wave of substantial policy measures that may well rival the level of fiscal support offered during the pandemic.

The most recent example came in the UK, with the announcement that the government would cap average bills to an annual cost of £2,500. The likely cost is set to be eye-watering but, as shown by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the intervention is not effectively targeted, with the biggest (absolute) gains set to be enjoyed by high-income households.

Going forward, uncertainty reigns as the path of wholesale energy prices intertwines with geopolitics. When evaluating policy, managing the tension that might exist between the need to most effectively target fiscal support with a desire for simplicity will need to be carefully navigated.

In the longer term, however, more elevated government debt levels suggest that policy-makers might usefully focus on how they can encourage households to build financial resilience during periods of relative economic calm. As the past three years have so amply demonstrated, the next “rainy day” could be just around the corner.

Author

Phil Thornton

Economics Editor

+44 (0) 7941 443 781

Phil Thornton

Economics Editor

London, United Kingdom

Phil oversees editorial standards across all Oxford Economics’ consulting and cities and regions projects.

Prior to joining the company in 2021, he ran a consultancy business Clarity Economics that produced reports, op-eds, and analysis pieces for a wide range of clients and media outlets. Previously he was an economics correspondent at The Independent newspaper in London, where he wrote news stories, features, and comment articles. He was also night editor, business news editor, and transport correspondent at the paper.

He received the Workworld Media Award for Print Journalist of the Year in 2006 and for Feature Writer of the Year in 2009. He has a degree in law from University College London.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Europe: Nuclear energy has likely peaked, despite a new embrace

The energy crisis has provoked a fundamental rethink of nuclear energy across Europe and many governments are now committing to building new reactors or delaying phaseouts. But we estimate phaseouts will still offset new additions for some years.

Find Out More

Post

Further industrial gas savings would come at steep cost for Germany

German industry has been successful in reducing its consumption of gas relative to previous years, particularly in the second half of the year.

Find Out More

Post

Services inflation to take centre stage in 2023

Over 2023, we expect global food, energy, and goods inflation to fall sharply. That said, the degree to which services inflation declines will also determine how quickly headline CPI inflation drops.

Find Out More