Blog | 01 Jul 2021

Does a greener economy mean longer-lasting inflation? Not necessarily

Stephen Foreman

Associate Director, Economic Impact

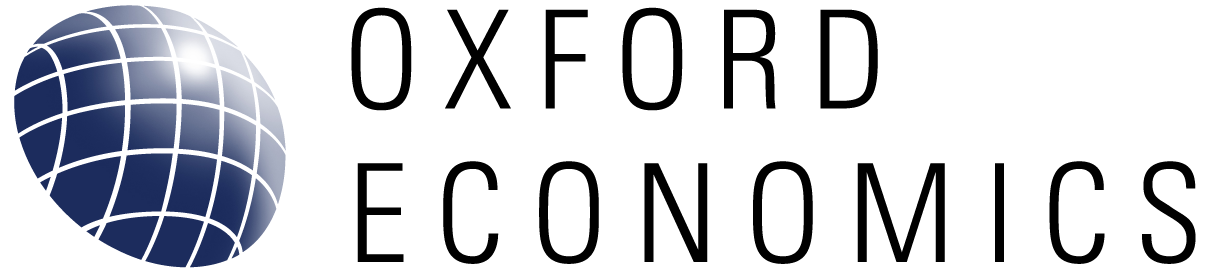

Commodity price surges were associated with spikes in inflation in the 1970s, but have not been so in recent decades. During the period before the creation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), for example, cheap oil encouraged households to purchase cars, while manufacturers benefitted from energy-intensive production techniques. Consequently, when oil prices quadrupled in 1973-74, that degree of energy dependence resulted in substantial inflation. Since the early 1990s, though, this relationship has evaporated as commodities’ role in the economy has declined and central banks have been more effective at keeping inflation expectations stable. None of the commodity price surges seen in the decades since has led to substantial rises in core inflation—in fact some have been associated with lower inflation.

Some argue that the push to decarbonise the economy may change this long-standing trend, because of the risk of a mismatch between climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals and technology. As Blackrock CEO Larry Fink said in June, “If our solution is entirely just to get a green world, we’re going to have much higher inflation, because we do not have the technology to do all this yet.”

Some argue that the push to decarbonise the economy may change this long-standing trend, because of the risk of a mismatch between climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals and technology. As Blackrock CEO Larry Fink said in June, “If our solution is entirely just to get a green world, we’re going to have much higher inflation, because we do not have the technology to do all this yet.”

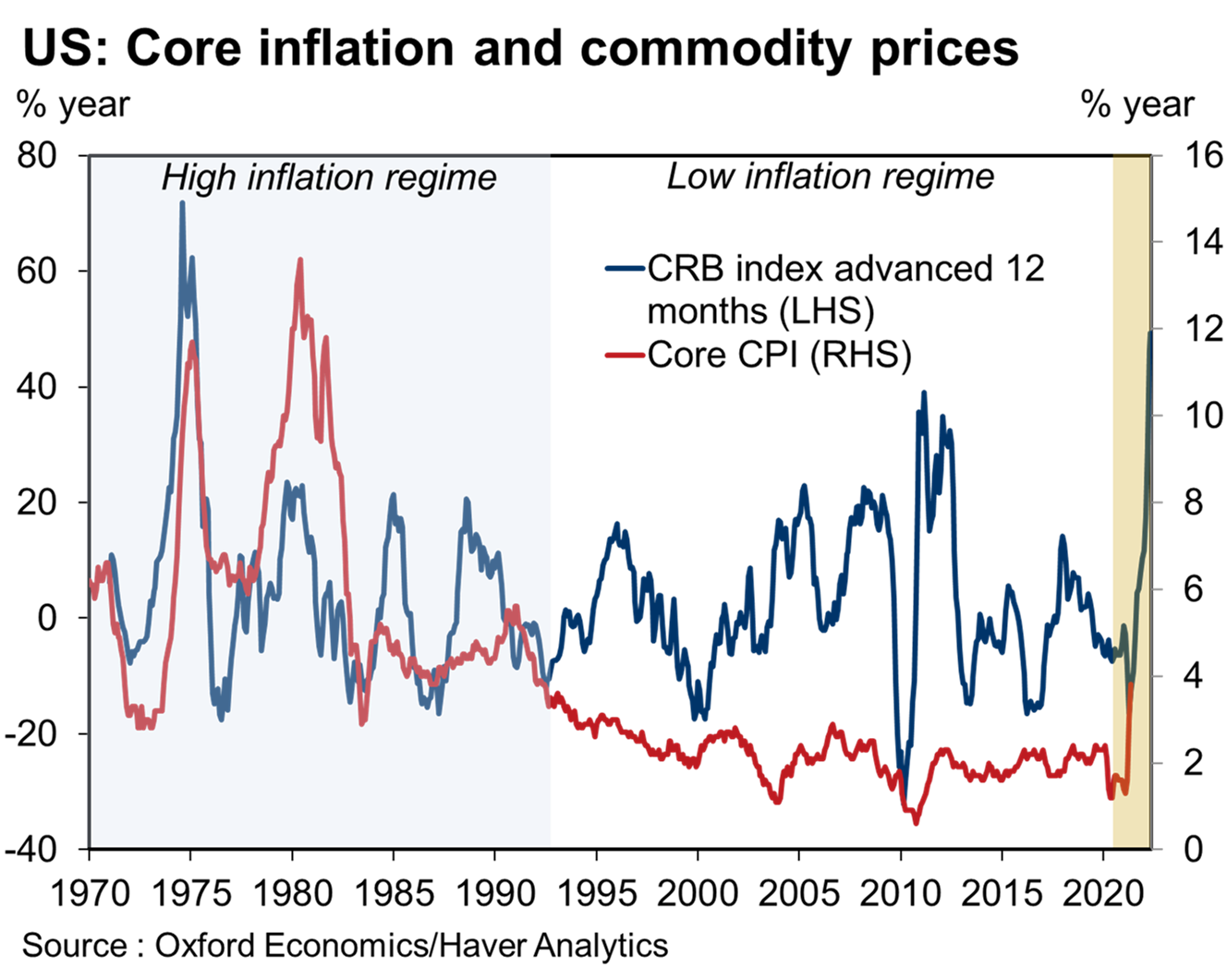

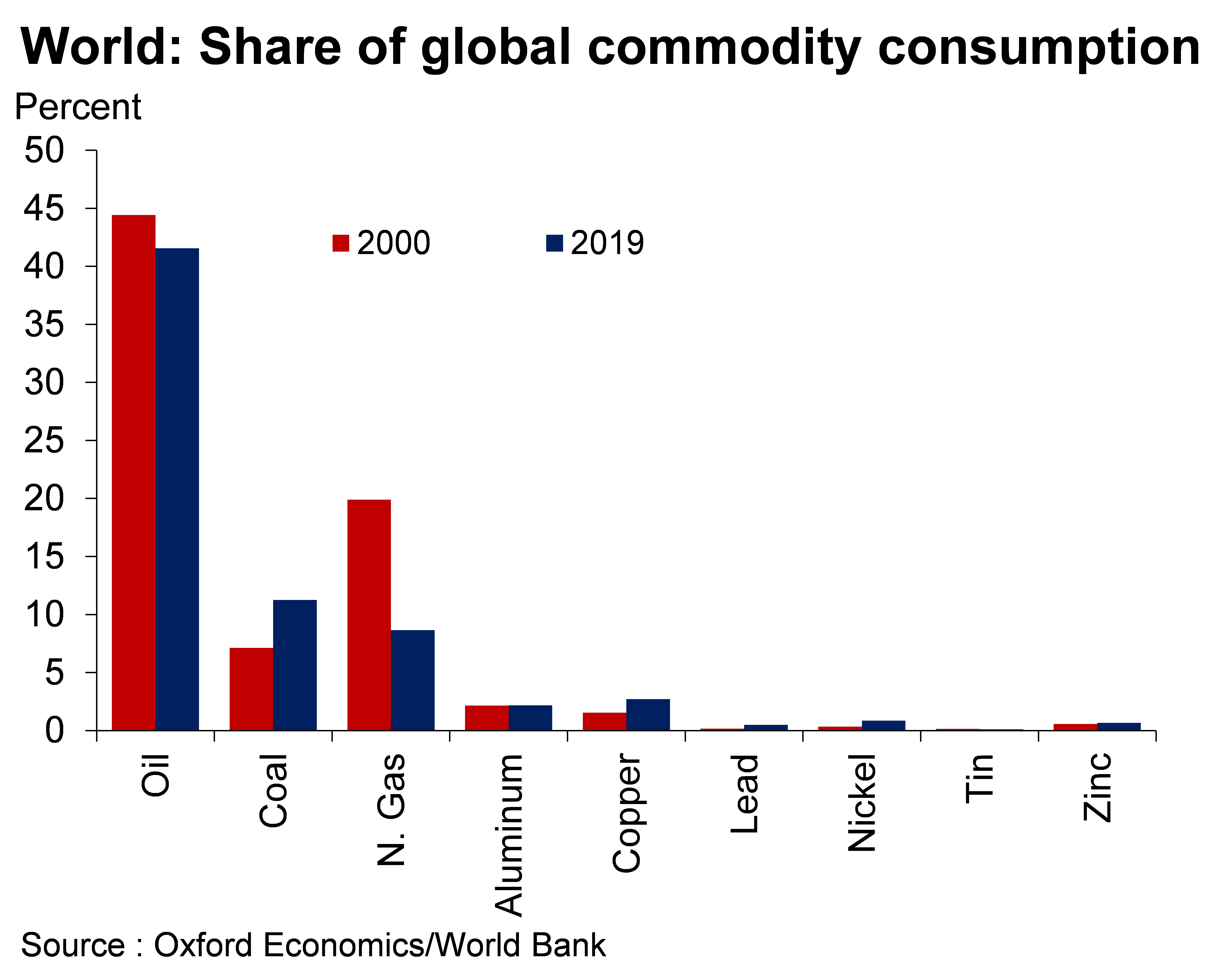

Take the surge in sales of electric vehicles, which require at least three times more copper than traditional vehicles. Copper currently accounts for just 3% of global commodity consumption, but the expansion of renewable energy capacity is likely to significantly increase copper demand. This rising role of copper has led some to suggest that copper will be to the 21st century what oil was to the 20th.

Whilst we agree that copper, and other green commodities will play a crucial role in the future economy, we’re more sceptical that they will take the same prominence as oil over the next few years. In contrast with copper, oil accounts for roughly 40% of current commodity consumption, and is likely to only see a very gradual decline in demand ahead. Other green commodities such as nickel and tin represent just 1% and 0.1% of commodity consumption respectively. So even with a rapid expansion in demand over the next few years, copper and other green commodities are likely to continue to represent a comparatively limited role in global economic activity relative to oil, limiting their impact on inflation.

Also, the currently elevated copper price, up roughly 70% relative to pre-pandemic levels, is not due solely to these environmental structural shifts, in our opinion. The price surge more reflects a lack of short-term supply due to pandemic-related disruptions for producers, and an excess of financial speculation. Also, as significant a change as the shift to green energy is, it will still take a while for electric vehicles to become dominant in the marketplace, and for extra spending on electric grids to build up.

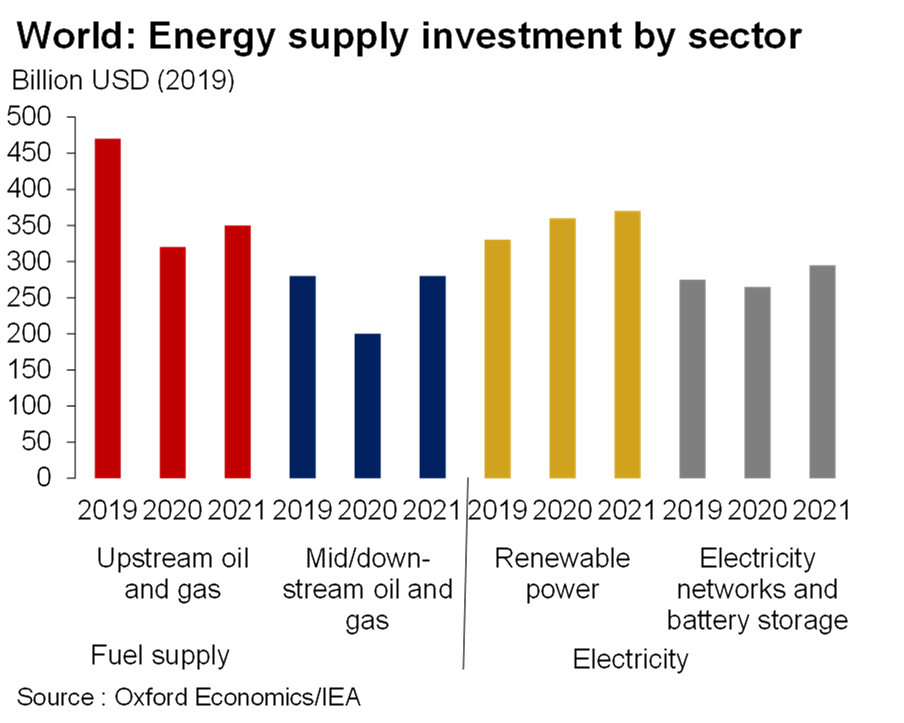

The push to decarbonise has also affected investment in fossil fuels, with companies under pressure to keep investment in fossil fuel expansion in check. With a potentially shrinking market, expansion in this sector may appear less lucrative. However, if future energy demand is not sufficiently met by greener energy sources, production of fossil fuels such as oil could fall short of demand, raising the risk of price increases.

Overall, the transition to a greener economy through changes in government climate policy, investment, technology, and consumer preferences may create inflationary threats. However, given the decreasing role of commodities in determining inflation over the past several decades, and generally well-anchored inflation expectations, a shift to a 1970s-style period of inflation via this channel is unlikely to happen overnight, and would take an accumulation of policy errors and further price shocks. This will be a big policy issue to focus on going forward, to minimise the risk of the green energy transition inadvertently creating spiralling price pressures across the economy.

Overall, the transition to a greener economy through changes in government climate policy, investment, technology, and consumer preferences may create inflationary threats. However, given the decreasing role of commodities in determining inflation over the past several decades, and generally well-anchored inflation expectations, a shift to a 1970s-style period of inflation via this channel is unlikely to happen overnight, and would take an accumulation of policy errors and further price shocks. This will be a big policy issue to focus on going forward, to minimise the risk of the green energy transition inadvertently creating spiralling price pressures across the economy.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

MENA – Latest Trends

Our blog will allow you to keep abreast of all the latest regional developments and trends as we share with you a selection of our latest economic analysis and forecasts. To provide you with the most insightful and incisive reports we combine our global expertise in forecasting and analysis with the local knowledge of our team of economists.

Find Out More

Post

You don’t have to be an IT expert to lead on AI

The adoption curve for AI will vary across companies but, according to our data, it’s probably already in use in customer service and marketing—areas where women are more likely to hold leadership roles.

Find Out More

Post

The latest export from China is … deflation

We expect Chinese export price deflation to provide a helpful tailwind in the struggle to bring EM inflation back to target.

Find Out More