Blog | 25 Mar 2022

Africa’s energy conundrum: What we can learn from a small mountainous enclave

Jacques Nel

Head of Africa Macro

A small mountainous kingdom at the southern tip of Africa has demonstrated how the world’s most energy-starved region can develop while not contributing its ‘fair share’ to climate change. The Lesotho Electricity Company and the Lesotho government recently entered into an agreement with a consortium to develop the country’s first independent power producer (IPP) project. The parties concluded a 25-year power purchase agreement (PPA), as well as the related connection and implementation agreements, for a 20-megawatt (MW) solar photovoltaic (PV) plant to be developed, operated, and owned by a partnership of international and local private sector firms. The project will be funded by the UK Renewable Energy Performance Platform with equity support from the Norwegian Investment Fund (Norfund), Lesotho Pension Fund, Scatec, One Power Lesotho, and Izuba Energy.

A small energy project in a small African nation might seem insignificant, but it represents a potential blueprint for how the continent can traverse a critical developmental hurdle, and for multilateral/bilateral engagement on the continent.

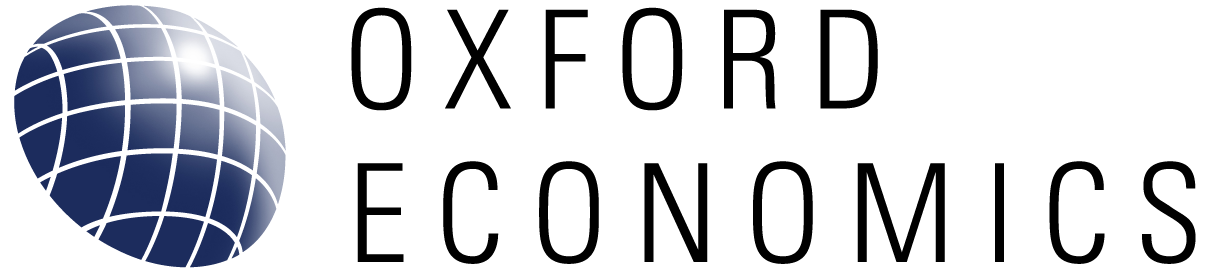

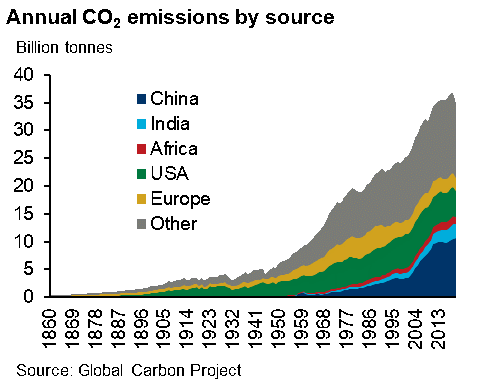

Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest electrification rate on the planet: Only an estimated 46.7% of the regional population has access to electricity, with some countries such as South Sudan and Chad recording figures under 10%. Largely due to this lack of reliable and accessible electricity, Africa contributed less than 4% to global CO2 emissions in 2020 despite accounting for around 17% of the global population. Addressing the lack of access to electricity without pushing up the continent’s carbon footprint too aggressively represents a clear developmental challenge with global consequences. Meanwhile, government efforts to improve energy infrastructure are obstructed by fiscal constraints, which have intensified due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, short-term financial considerations and vested interests have prevented some countries from going the greenest route. This could remain the case going forward.

The proliferation of IPPs in the renewable energy space has the potential to address a number of these issues. Leveraging private capital and expertise to produce, distribute, and trade energy from renewable resources will improve access to electricity while containing countries’ carbon footprints. One concern is that these IPP arrangements often entail off-take agreements with national state-owned utilities, which require financial guarantees as a risk mitigation measure to attract private investment. These guarantees generally expose indebted governments to additional contingent liabilities. However, if more multilateral and bilateral agencies are able to ‘de-risk’ these projects, taking on the contingent liabilities following a process of due diligence, this would create a context in which private capital can fund low-carbon electrification without the risk of further weighing on domestic finances.

The signing of an IPP is by no means a silver bullet. Some projects in some regions might just not be financially feasible, while tariff escalations linked to high consumer price inflation could become unaffordable. It is therefore important to design and optimise IPP frameworks in accordance with national circumstances and project lifetime affordability, and in the best long-term interests of electricity consumers. Furthermore, the cost of de-risking a project increases with the number and the nature of the risks involved, so effective partnerships between multilateral/bilateral agencies and domestic governments will be critical. Agreement conditionality will be the first step towards de-risking. But if the tiny kingdom of Lesotho can do it, there is hope that the rest of the continent, with its highly constrained electricity industries and strained government balance sheets, can follow suit.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Mapping the Plastics Value Chain: A framework to understand the socio-economic impacts of a production cap on virgin plastics

The International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA) commissioned Oxford Economics to undertake a research program to explore the socio-economic and environmental implications of policy interventions that could be used to reduce plastic pollution, with a focus on a global production cap on primary plastic polymers.

Find Out More

Post

How Canada’s wildfires could affect American house prices

The Northern Hemisphere is now heading into the 2024 fire season, having just had its hottest winter on record. If it is anything like last year, we can expect to see further impacts on people, nature, and global markets.

Find Out More

Post

Beyond assumptions – the dynamics of climate migration

Millions of people have already been displaced because of environmental shocks, but many aspects of climate migration remain poorly understood. This confusion has led to oversimplified assumptions about its causes and effects – in reality, it’s more complicated and has many nuances.

Find Out More