Blog | 13 May 2021

Quantitative Easing: Time heals all wounds (hopefully)

In his recent blog post, James Nixon argued that the exit from the current round of pandemic-driven QE may be anything other than smooth. In particular, he highlighted that bond yields rising from their current rock-bottom level could trigger a volatile rush for the exit by bond investors and undermine sovereigns’ debt sustainability.

Arguably, the eurozone is one of the economies most exposed to those risks around the world. With the GDP-weighted average yield on 10-year governments close to zero, investors could face a particularly harsh awakening should yields rise sharply. And while the aggregate public debt level in the region isn’t particularly worrisome (at around 100% of GDP) compared with other advanced economies, that isn’t saying much when said average includes Italy—the country that owes a staggering 160% of its GDP. Combine that with anaemic growth prospects on the back of weak demographics as well as an insufficient institutional setup to respond to future crises and you have a fairly toxic cocktail.

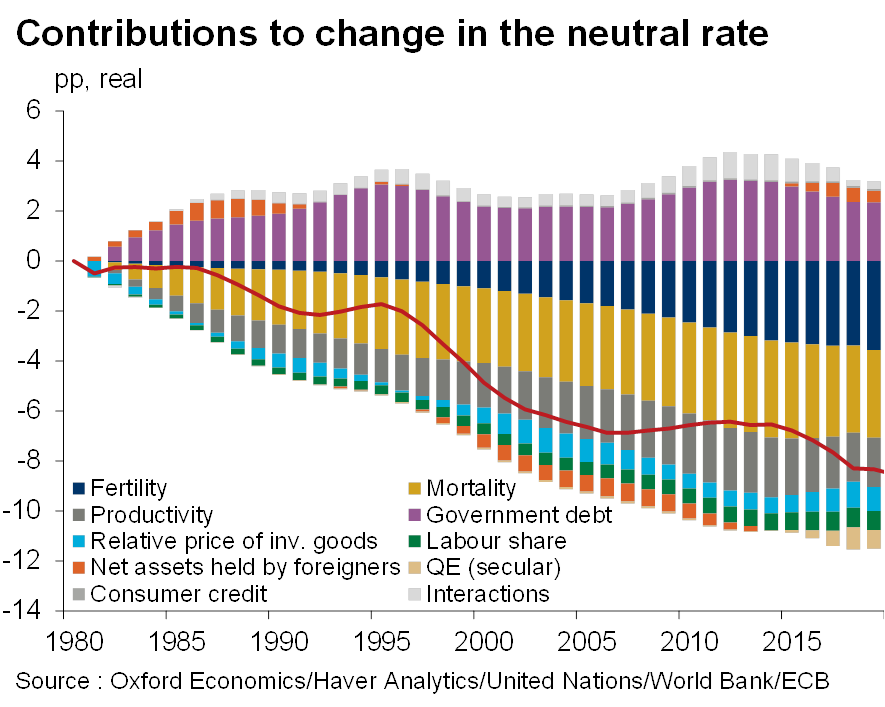

However, central banks will operate in a unique environment over the coming years that should facilitate their eventual exit from current policies. For example, there is good reason to believe structural headwinds such as an aging population, falling productivity growth and a global savings glut have led to a shortfall in aggregate demand and a structural downtrend in interest rates. Indeed, our detailed modelling shows QE to have contributed only a small part to that fall in yields. These headwinds for yields are particularly entrenched in the eurozone, which will likely remain stuck in secular stagnation for the coming decade.

Viewed through that lens, QE assumes an additional function: reinforcing the central bank’s forward guidance on policy rates. Indeed, while the ECB is likely to abandon its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) sometime next year, the central bank has also said for a while that it will exit its standard asset purchase program only shortly before policy rates will rise. In other words, secular stagnation will keep policy rates so low for so long as to imply a yield curve that will remain flat by historic standards over the medium-term. Investors have long internalized that message, which should reduce the risk of harmful rush to the exit. A gradual rise in yields should also not be a big risk to debt sustainability, because the immediate impact on the interest rate burden is muted by the fact that the average weighted maturity of eurozone governments’ outstanding debt has risen by more than a year to about eight years since QE started. This isn’t to say that there won’t be bumps in the road—fiscal sustainability will remain one of Europe’s key challenges. But to stick with James’ metaphor: The “politicised house of cards” that central banks built with QE may, for better or for worse, be much less shaky than some fear.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Global Cruise Trends Report: March 2024

This report delves into research conducted in Q4 2023 across five key cruise markets, all indicating strong cruise demand. Our comprehensive market intelligence aims to equip the travel industry with insights into the significant growth potential in the cruise industry.

Find Out More

Post

The Deglobalisation Myth: How Asia’s supply chains are changing

Despite talk of deglobalisation, a quantitative analysis of intermediate goods show global supply chains have continued to expand in the last five years. Amid a volatile world economy, swiftly evolving supply chains are minting new winners and losers in global trade.

Find Out More