Blog | 09 Apr 2021

Is this time different, or an exercise in financial folly?

Irmgard Erasmus

Senior Financial Economist, Oxford Economics Africa

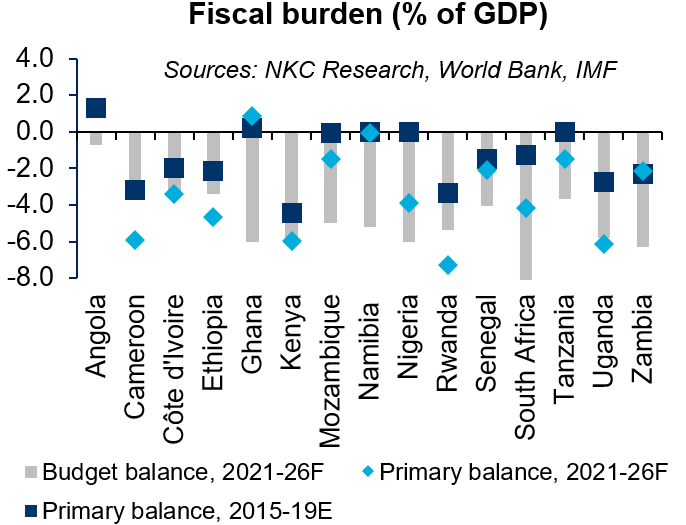

As John Templeton once said, the four most dangerous words in investing are “this time it’s different.” This notion seems to affect each forthcoming generation, with regulators hypothesising that fundamental changes to economic and financial systems—usually through technological advancement or broadening of the policy toolkit—will allow for greater protection against traditional market risks. Recent arguments by policy-makers in Africa suggest that rapid financial innovation and liberalisation have rendered widening twin deficits, unfettered public borrowing and low domestic savings rates as non-issues—or, at worst, tolerable—as an increasingly sophisticated policy framework and integrated global financial market are equipped to handle these “better than before.” Indeed, market complacency is again creeping in as the global financial system, awash with inexpensive liquidity, allows weaker-quality creditors to tap international debt markets as a dearth of domestic savings is set against ballooning fiscal deficits.

Borne out of economic necessity, African regulators rightly unleashed countercyclical monetary and fiscal measures to dampen the impact of Covid-19 demand and supply shocks. Unlike earlier crises, the policy toolkit was much deeper this time around, including reductions in reserve requirements, adjustments to standing facilities, restrictions on repatriations by the banking sector, expanding the pool of eligible collateral in operations, bond purchases on the primary market, and opening liquidity lines with the Fed. The deployment of countercyclical, above-the-line measures (higher public spending and tax relief), meanwhile, was limited by a dire lack of fiscal space due to weak pre-pandemic solvency and liquidity indicators. Pre-2020, the growth model in a number of African countries primarily relied upon a debt-fuelled public capex strategy, with slow rotation towards private capital as a primary driver of growth. This contributed to thinning fiscal buffers, but global market complacency ensured steady access to the global funding glut. Across the globe, below-the-line measures (such as loan and equity stakes) and guarantees formed an important part of Covid-19 policy support, but the large informal sector, red tape and implementation challenges limited the efficacy of this avenue in African countries.

Lower foreign participation in primary market auctions, the absence of a local savings glut, and limited leeway to repurpose budgetary funds steered African fiscal authorities to external (commercial, concessional and grant) sources to bridge the residual funding gap. What might the problem be post-Covid? We fear that the jump in public discretionary consumption may drive a further divergence between money supply (up) and private sector credit extension (down), with the added jolt of risk aversion feeding into a burgeoning crowding-out problem. Merely tapping the external funding glut to meet budgetary shortfalls will become more challenging as advanced economies move toward monetary policy normalisation in 2022/23.

Lower foreign participation in primary market auctions, the absence of a local savings glut, and limited leeway to repurpose budgetary funds steered African fiscal authorities to external (commercial, concessional and grant) sources to bridge the residual funding gap. What might the problem be post-Covid? We fear that the jump in public discretionary consumption may drive a further divergence between money supply (up) and private sector credit extension (down), with the added jolt of risk aversion feeding into a burgeoning crowding-out problem. Merely tapping the external funding glut to meet budgetary shortfalls will become more challenging as advanced economies move toward monetary policy normalisation in 2022/23.

Will the upcoming phase “be different”—creditors dismissing the red flags of ballooning fiscal deficits and slow recovery in revenue sources, continuing to fund the gap amid yield-seeking? Time will tell, but history suggests not.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

MENA – Latest Trends

Our blog will allow you to keep abreast of all the latest regional developments and trends as we share with you a selection of our latest economic analysis and forecasts. To provide you with the most insightful and incisive reports we combine our global expertise in forecasting and analysis with the local knowledge of our team of economists.

Find Out More

Post

BoJ to raise its policy rate cautiously to 1% by 2028

We now project that the Bank of Japan will start to raise its policy rate next spring assuming another robust wage settlement at the Spring Negotiation. If inflation remains on a path towards 2%, the BoJ will likely raise rates cautiously to a terminal rate of around 1% in 2028.

Find Out More

Post

How inflation eroded governments’ debts and why it matters

The supply-shocks era represented the first time in a generation where inflation significantly eroded the real value of global public debt. For EMs, the erosion averaged 3.7% of GDP between 2020 and 2023; the average for advanced economies (AEs) was twice that (7.3% of GDP).

Find Out More