Blog | 21 May 2021

Increased digitisation could exacerbate inequality in Southern Africa

The imposition of lockdown regulations to prevent the spread of Covid-19 forced millions of people across the globe to work from home. The transition was far smoother for “knowledge workers” (employees who sell their intellectual labour) than those who sell their manual labour. The shift was also obviously easier for those who have internet access: Only an average of 28% of national populations have internet access in Southern Africa, which is well below the world average of 51%, according to the United Nations International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

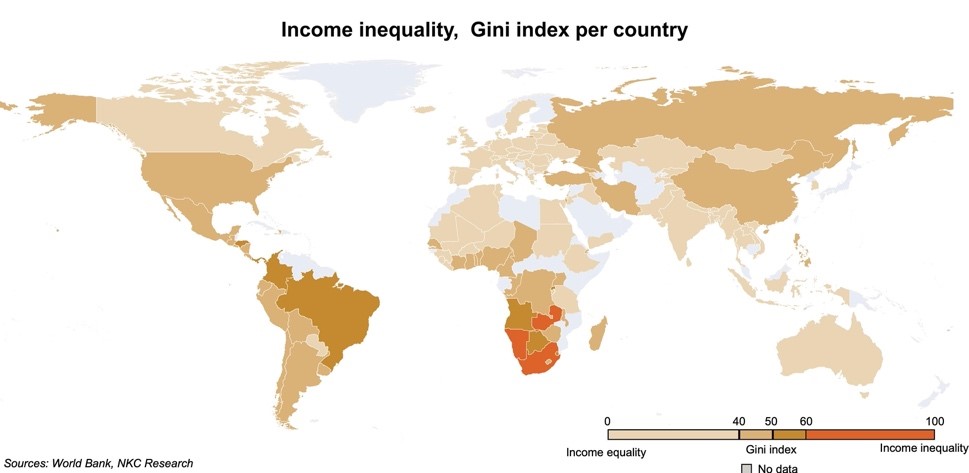

One of the legacies of the coronavirus pandemic will be increased digitisation and automation of work that was once done manually by people. This may have a particularly significant impact on employability of younger workers in Southern Africa, where inequality is already staggeringly high: South Africa’s Gini Index rating (a measure of a country’s level of income inequality) is 63.4—the highest in the world. Namibia’s is 61.0 and Botswana’s is 60.5. A large portion of the youth was already unemployed before the pandemic—according to 2019 figures from the International Labour Organisation (ILO), South Africa has the highest unemployment rate (55.7%) among workers aged 15 to 24 in the world. Neighbouring states Eswatini (47.4%), Namibia (41.2%) and Botswana (38.0%) also rank in the top ten. It is important to pay attention to these statistics now, as they will shape the future of inequality in the post-Covid world.

The digitisation of education will also contribute to increasing inequality. While it is too soon to quantify the impact of the coronavirus on the school drop-out rate, there are reasons to expect the impact to be negative in Southern Africa. There are undoubtedly students from lower-income families who do not have internet access at home or who have had to dedicate their time to working to support their families as economic conditions worsened. These students have lost the opportunity to upskill themselves. In turn, students from higher-income families have been able to continue their education without these limitations and consequently will be able to sell their intellectual labour in a more digitised world.

Increasing inequality within Southern African states will contribute to these states being left behind in the global economic recovery. To overcome this, governments should invest more in the development of internet infrastructure in low-income areas to increase internet access. They should also invest more in opening up education opportunities for people from low-income backgrounds, such as offering more scholarships and bursary schemes. This will enable a larger portion of the population to move towards becoming knowledge workers in an increasingly digitised post-Covid world.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Oxford Economics Expands Regional Presence with the Launch of Chinese Website

Over the past six years we've maintained the unique modelling and analysis that clients and the media have come to rely on from BIS Shrapnel while incorporating Oxford Economics' rigorous global modelling and analytical framework to complement it," said David Walker, Director, Oxford Economics Australia.

Find Out More

Post

Oxford Economics Introduces Proprietary Data Service

Oxford Economics is excited to enrich its suite of asset management solutions with the introduction of the Proprietary Data Service.

Find Out More

Post

Australia: RBA hike by another 25 bps as the fight against inflation continues

The RBA has raised its cash rate target by a further 25 basis points, taking it to 4.1%. Although inflation has peaked, the RBA board is still clearly uncomfortable with its brisk pace.

Find Out More