Blog | 01 Nov 2021

Fixating on debt size misses a prime opportunity

Gabriel Sterne

Head of Global Emerging Markets

The legacy of the massive fiscal response to the pandemic is ballooning government debt. From 2019 to today, average government debt has leapt by 9% of GDP in emerging markets (EMs) and a whopping 20% in advanced economies (AEs). Now, average debt-to-GDP ratios are over 60% in EMs and double that in AEs.

At least in the case of public debt, too much focus on the size of debt and the urgency of overall adjustment could lead to sub-optimal policies. In particular, it may distract global governments from the crucial issue of improving the quality of tax policies to foster sustainable growth, a key topic debated by a panel hosted by the International Tax and Investment Center at this year’s IMF annual meetings. More on that below.

But first, let’s look at the case for overall adjustment. Our main argument here is that most economies can stabilise debt-to-GDP ratios around current levels with only moderate fiscal effort. The relevant concept here is the so-called debt-stabilising primary balance, which is the fiscal balance excluding interest payments that you need to run over the medium term to prevent debt inexorably rising.

One reason to like this concept is that it brings the issue back to politics. How much fiscal effort can societies tolerate before even reform-minded politicians feel too much heat? In the 2010-2012 Greek debt crisis, for example, even the IMF balked at demanding a primary surplus of more than 3% of GDP, a useful benchmark for the limits of social acceptance.

Most governments remain far from that boundary. Our own global debt sustainability analysis is based on IMF methodology in which paths for debt-to-GDP are determined by developments in real interest rates, growth, inflation, and the fiscal deficit. It suggests very few governments need to run primary surpluses. Indeed, our analysis suggests the average government can still afford to run quite big primary deficits: 3.9% of GDP in EMs, and 3.5% in AEs would stabilise 2030 debt-to-GDP ratios at 2021 levels.

That’s not so onerous, and the point is that the impact of higher debt levels on debt servicing costs has in recent years been offset by falling global interest rates.

But what if interest rates spike higher via a sustained bout of global stagflation? Even when we run such a nightmare scenario—which among other things could see real bond yields on all government debt increase by 100bps—we find that EMs can still stabilise debt at 2021 levels by running quite palatable primary deficits of 3.1% of GDP. For AEs, the figure is 2.1%.

An important reason to be sanguine is that global funding conditions have improved immeasurably in recent years and few governments face refinancing issues. It’s not just the major central banks; the funding capacity of EMs’ domestic financial systems has rocketed. And most importantly, our research suggests that as the global population ages the high stocks of savings will keep global interest rates very low for another three decades.

That said, we do see two categories of concern in governments’ overall fiscal positions. The first is that with so much savings chasing the debt, the era of very low interest rates implies weak market discipline on fiscal policies will continue for a good while longer. If you worry about the size of debt now, you may be worrying even more in a decade.

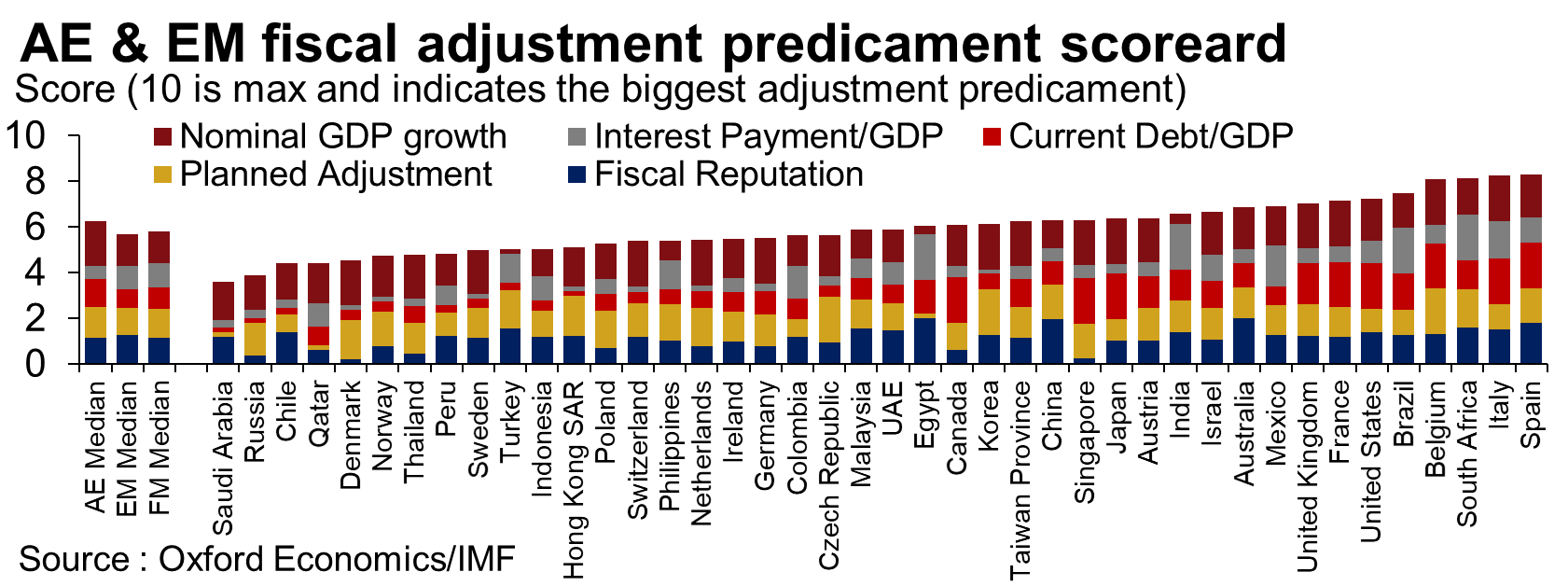

Second, some governments face a much more severe fiscal predicament than the averages suggest. To understand governments’ fiscal health, we have developed a scorecard that includes not only the key macro drivers of debt sustainability, but also measures of the ambition for fiscal adjustment and reputation for meeting fiscal projections in the last decade.

Some of these rankings may come as a surprise, at both ends of the spectrum. The five governments facing the most difficult fiscal predicaments are Spain, Italy, South Africa, Belgium, and Brazil (see chart). Among frontier markets [not included on this chart], Sri Lanka and El Salvador are of particular concern.

But while few countries face major fiscal sustainability predicaments, many others could do more to address an area of more widespread deficiency—the quality of fiscal policies.

The good news is that higher post-Covid debt levels need not push most policymakers into rash fiscal choices, either via sacrificing key welfare support or infrastructure investment, or by delaying the drive to improve the quality of tax policies. But the need to increase the quantity and quality of revenues remains, as it has for many years, an urgent issue on which progress has been patchy. This is particularly so in lower income economies, where Covid has derailed implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In its Fiscal Monitors, the IMF has been correct to highlight the need for strong national ownership to prioritize SDGs and improve efficiency, and for the international community to provide additional support.

In short, we see no need for the pandemic to lead to a departure from three basic principles:

1: Business taxes should avoid discouraging work, investment, and risk-taking.

2: Tax reform should lead to lower compliance and administrative costs.

3: Taxes should be fair and competitive—best achieved by having similar tax burdens on all business activities at the lowest possible rates, and scaling back preferential treatment in favour of lower general income tax rates.

These goals have been around for decades and there remains much to do; we hope more governments can rally round the improvement drive.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Trumponomics – the economics of a second Trump presidency | Beyond the Headlines

The 2024 US Presidential Election is less than seven months away. In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Bernard Yaros, Lead Economist, outlines two scenarios for the US economy if former President Donald Trump returns to the White House and Republicans sweep Congress.

Find Out More

Post

Global Trade Education: The role of private philanthropy

Global trade can amplify economic development and poverty alleviation. Capable leaders are required to put in place enabling conditions for trade, but currently these skills are underprovided in developing countries. For philanthropists, investing in trade leadership talent through graduate-level scholarships is an opportunity to make meaningful contributions that can multiply and sustain global economic development.

Find Out More

Post

Mapping the Plastics Value Chain: A framework to understand the socio-economic impacts of a production cap on virgin plastics

The International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA) commissioned Oxford Economics to undertake a research program to explore the socio-economic and environmental implications of policy interventions that could be used to reduce plastic pollution, with a focus on a global production cap on primary plastic polymers.

Find Out More