Blog | 27 Apr 2022

Too much of a good thing? Fiscal stimulus in the global construction market

Thomas Westrup

Senior Economist, OE Australia

Fiscal stimulus remains an important chapter in the economic playbook. Governments worldwide have set their sights firmly on public infrastructure investment as a means to spark demand and employment following the coronavirus-induced economic downturn. The benefits of infrastructure investment are underpinned by the key assumption that projects can be delivered on time, on budget and on scope. But what if the avalanche of project announcements and growing pipeline of work is too great for local or global supply chains to keep up?

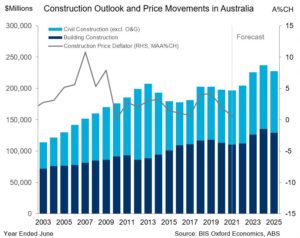

As supercharged infrastructure construction demand is set to push total construction market activity beyond previous peaks, there is no guarantee that supply will be able to rise to the occasion. In Australia, this has been highlighted by Infrastructure Australia in their recent Market Capacity Report, wherein a near doubling in public infrastructure investment over the next three years will drive exceptional increases in demand for labour, plant, equipment and materials.

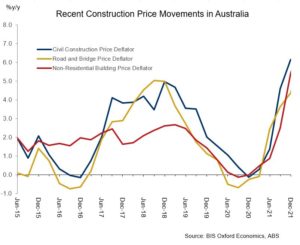

Capacity issues have been further exacerbated by the unique challenges of the coronavirus outbreak—varying levels of movement restrictions on internal and overseas migration have limited key sources of skilled labour over the past two years. Other factors such as volatile commodity prices and the disruption of international supply chains are already straining capacity and raising resource costs. These constraints can be amplified in regional areas, where supply chains are generally geared to cater to a particular (usually mild) level of demand. Further tightening amongst domestic resource markets, in combination with existing capacity challenges, would work to deliver a sustained period of high escalation rates across the entire industry. This challenge has been faced before—in Australia, periods of supranormal growth in construction during the mining boom drove large increases in wages and other local input costs. In tandem, exceptional strength in global oil and steel prices drove construction cost growth well above inflation, peaking at over 10% in the late 2000s.

This challenge has been faced before—in Australia, periods of supranormal growth in construction during the mining boom drove large increases in wages and other local input costs. In tandem, exceptional strength in global oil and steel prices drove construction cost growth well above inflation, peaking at over 10% in the late 2000s.

There are substantial consequences of failure if supply chains fail to meet the demand challenge, beyond the financial health of the supplying firms themselves and the sustainability of the construction industry. Long periods of high cost escalation will increase the prevalence of cost overruns or project failures. This isn’t isolated to new builds; the operations and maintenance of existing infrastructure will exceed budgeted expectations due to overlapping inputs.

Ultimately, severe delays or project overruns will lower the efficacy of stimulus measures, shifting the public spending into periods where they economy has already recovered. The taxpayer is the eventual loser as resource price increases erode the value-for-money delivery of infrastructure, and increased spending flows through to higher costs rather than higher real activity.

The increasing saturation of global construction markets in an industry with historically poor productivity growth globally suggests that governments should place greater emphasis on ensuring either that capacity can rise to meet forthcoming demand or that infrastructure is procured or delivered more productivity to ensure that scarce inputs are put to effective use.

Developing a highly visible, sustained long-term pipeline of funded infrastructure would help shift the sector away from the steep peaks and troughs that hamper industry confidence and productivity. A sustained pipeline of works, particularly in regional and remote areas, provides the security for businesses to invest in their own capacity and allows skilled labour to be more easily attracted and retained over time. Governments can also play a transformative role in raising productivity, including procurement reforms, productivity enhancing technologies, and enhanced flexibility and coordination in delivery.

Beyond this, governments could consider more direct intervention in the market—identifying risks and potential supply “pinch points” by developing comprehensive assessments of capacity across construction resources and regions. Combined with a richer understanding of future resource requirements, this would allow for targeted investment and policy shifts to alleviate specific supply bottlenecks.

Ultimately, this requires a shift in mindset. As major economies navigate towards sustainable economic recovery and growth, attention will need to divert from using infrastructure to boost demand and employment to making productivity and supply the “new sexy.”

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Future of Construction

Future of Construction gives forecasts for global construction to 2030 as well as perspectives on climate-related challenges for the construction industry.

Find Out More

Post

Policy-makers bet on construction to escape COVID economic shock

The construction sector did not escape the coronavirus-induced economic downdraft unscathed. Activity at the global scale fell 1.4% in 2020, with much steeper declines in countries that imposed harsher restrictions. But things are changing.

Find Out More

Post

The Future of Australian Infrastructure: Australia’s Global Competitiveness

The current investment in Australian infrastructure is barely keeping pace with demand. To meet future demand we will need to invest more but also, crucially, build and operate major assets more efficiently.

Find Out More